The Free French in London

Forces Françaises Libres

Memories of wartime London (1942-43)

by François Charles-Roux with additional notes by Christopher Long

The French diplomat and ambassador, François Charles-Roux (1909-99) was an aide-de-camp to General Charles de Gaulle during World War ll. From 1942-43 he served de Gaulle at the headquarters of the Forces Françaises Libres (FFL) 'government in exile' in Carlton Gardens, London, remaining a key member of the FFL until the Liberation of France in 1944.

In 1984 he was asked by his cousin, Christopher Long – then working on a study of Charles de Gaulle – to write this account of the London period. Charles-Roux is characteristically 'diplomatic', which is unfortunate since he was an intimate witness to a diplomatic catastrophe which came to colour France's foreign policies world-wide and to have an enduring, negative effect on Anglo-French and Franco-American relationships. Charles-Roux touches on this towards the end of this article when referring to the assassination of Admiral Darlan.

Secret Papers: Escape & Evasion in Occupied France

Charles de Gaulle – The Man Who Stood Alone

From 1940-42 de Gaulle, along with his FFL, received a cautiously warm welcome from Winston Churchill. François Charles-Roux, on the other hand, had particularly warm and close connections with England and the English through his marriage to Fanny Zarifi and her numerous well-placed relations in London.

From 1940-42 de Gaulle, along with his FFL, received a cautiously warm welcome from Winston Churchill. François Charles-Roux, on the other hand, had particularly warm and close connections with England and the English through his marriage to Fanny Zarifi and her numerous well-placed relations in London.

But, from 1942 onwards, de Gaulle met out-right distrust and antagonism on the part of Roosevelt and the United States. This was deeply resented by the FFL since the USA had effectively avoided entering the European war until 1942/43 – and only after she was herself attacked in 1941 – more than two years after the war had started and almost two years after de Gaulle had arrived in London to rally support for the liberation of France.

In conversation with Christopher Long in 1984, François Charles-Roux privately conceded that de Gaulle remained, for the rest of his life, "deeply affronted by his wartime experience in Britain and of the United States in particular". This was to have an enduring impact on post-war world affairs.

Charles-Roux thought Churchill had only "some justification in some respects" for keeping the FFL at arm's length. The organisation's internal security was known to be weak and deeply penetrated by agents of the quasi-Nazi 'Vichy' government in occupied France – as well as by communist agents whose agenda was diametrically opposed to that of de Gaulle, Britain and the USA. Presumably, therefore, British intelligence agencies too had penetrated the FFL. Certainly much of its signals traffic was being intercepted and monitored. As an 'ally', de Gaulle resented this.

Charles-Roux maintained that de Gaulle was critical of Churchill's failure to prevent Roosevelt – and presumably Eisenhower – from alienating him in most of the Allies' strategic planning and operations. He was also resentful of Britain's unwillingness to involve the FFL in both its SOE/MI9/SIS activities behind German lines in France and the planning of the D-Day Normandy invasion.

Arrival in London

W

e arrived in London from Washington under a grey sky on a September evening in 1942. Having found one of those London taxis which so resemble a dowager's carriage, we headed for [No. 16] Porchester Terrace where we were due to live in the house of my wife's uncle, Michel Vlasto.

Through the taxi windows my wife and I observed the streets and the evidence of the blitz. Huge gaps here and there, crumbling walls and windows opening into blank spaces were appalling testimony to what the great city had suffered. But, despite the reduced traffic, normal good order seemed to reign. Nothing in the dress or comportment of passers-by hinted at nights spent in underground shelters without a change of clothes or to the tension caused by air-raids.

Through the taxi windows my wife and I observed the streets and the evidence of the blitz. Huge gaps here and there, crumbling walls and windows opening into blank spaces were appalling testimony to what the great city had suffered. But, despite the reduced traffic, normal good order seemed to reign. Nothing in the dress or comportment of passers-by hinted at nights spent in underground shelters without a change of clothes or to the tension caused by air-raids.

London in 1942-43 was not a comfortable environment for de Gaulle and the Free French where they were regarded with suspicion, particularly by the Americans. François Charles-Roux, aide-de-camp to de Gaulle from 1942, was more fortunate. He was married to Fanny Zarifi who had spent much of her childhood in England and had close family connections in London. Above: she is pictured centre in London in 1912, in the arms of her mother Antoinette 'Netta' Zarifi. With them are aunts and cousins of the Vlasto, Zarifi and Rodocanachi families. By 1942, in Occupied France, her aunt Fanny Rodocanachi (n&eacte;e Vlasto), (far right) was already deeply involved, with her husband George Rodocanachi, in the Pat O'Leary escape line which had its headquarters and safe house in their Marseilles apartment.

As soon as the taxi turned into Porchester Terrace I was struck by the number of closed-up houses. When it stopped in front of ours and our bags had been unloaded, we found ourselves alone in front of the now missing gate which had been removed for scrap [most iron gates and railings were taken for recycling into munitions] and we were deeply affected by a strange sense of sadness. The taxi drew away and, little by little, silence enveloped us as the sound of its engine faded. The garden, which was no longer separated from the street, seemed abandoned.

As soon as the taxi turned into Porchester Terrace I was struck by the number of closed-up houses. When it stopped in front of ours and our bags had been unloaded, we found ourselves alone in front of the now missing gate which had been removed for scrap [most iron gates and railings were taken for recycling into munitions] and we were deeply affected by a strange sense of sadness. The taxi drew away and, little by little, silence enveloped us as the sound of its engine faded. The garden, which was no longer separated from the street, seemed abandoned.

We carried our cases to the house. It was closed and, in the darkness, no light was visible through the closed shutters. We called out and our voices echoed in the silence of the street. At first no-one answered. After a while an old woman came out from the basement. She looked at us closely, as though we'd arrived from another planet, but had been warned of our arrival and opened the house for us.

No. 16 Porchester Terrace, Westminster, London, had already been hit by incendiary bombs by the time François & Fanny Charles-Roux settled there on their arrival in London in 1942. The house belonged to Fanny's uncle, Michel Vlasto (pictured below with his wife Chrissy), who had evacuated all his family and staff out of London. Later the Charles-Roux moved to Michel's mother's apartment nearby in the same street.

Crossing the threshold we were immediately struck by a strong smell of smoke. It wasn't the musty smell of long-closed houses. It was a mixture of the acrid stench of burnt timber and cleaning fluids.

Crossing the threshold we were immediately struck by a strong smell of smoke. It wasn't the musty smell of long-closed houses. It was a mixture of the acrid stench of burnt timber and cleaning fluids.

We didn't have to wait long for an explanation: before showing us to our first-floor rooms the house-keeper advised us to stay close to the wall as we climbed the stairs where, in the shadows, we saw that a whole section of the staircase was missing.

Right: Soon after the start of the German 'blitz' of London, Chrissy and Michael 'Michel' Vlasto took their elderly relatives and some of their servants to a farm in Surrey in order to "dig for victory". They left their large London house in Porchester Terrace, close to Kensington Gardens, for their children to use when on leave from the forces and it was here that Fanny & François Charles-Roux received a welcome of sorts when they first arrived in London. The house had already been hit by incendiary bombs.

It had been burnt, our guide explained, by an incendiary [phosphorous] bomb which she had single-handedly doused with sand from buckets kept for the purpose on each floor.

From the moment of our arrival we were witnesses to the courage and practicality of these Londoners whose cheerfulness and kind hospitality were evident over and over again during our stay in England.

The Free French

From the day after my arrival I was working at the Free French building in Carlton Gardens. It was a huge house on several floors, neither beautiful nor ugly, shared by all our departments. I had already been posted to the cultural section which formed part of the Foreign Affairs commission. My wife [Fanny Charles-Roux née Zarifi] offered her services and was taken on by the Interior commission where she was part of the team documenting the French Resistance within France.

From the day after my arrival I was working at the Free French building in Carlton Gardens. It was a huge house on several floors, neither beautiful nor ugly, shared by all our departments. I had already been posted to the cultural section which formed part of the Foreign Affairs commission. My wife [Fanny Charles-Roux née Zarifi] offered her services and was taken on by the Interior commission where she was part of the team documenting the French Resistance within France.

Right: General Charles de Gaulle

Much has been written about the Free French. General de Gaulle covers it magnificently in his memoirs. Others have described every aspect of it. I wouldn't dream of correcting or adding anything to the pictures they paint. I can only offer one more view and describe some episodes with which I was personally involved.

Ever since the arrival of this still small but fervent group which had followed General de Gaulle, one felt a deep sense of certainty in the ultimate victory of the Allies and hence our own country, just as the leader of 'Fighting France' had predicted in June 1940 [de Gaulle's famous 'appeal' to occupied France for support and resistance, broadcast by the BBC in June 1940].

Nevertheless, I remember a meeting, held around a map of Russia at the end of 1942, which included our representative in Kuybitchev. It was at the most poignant moment of the battle of Stalingrad and M. Garreau was explaining to us that if the German army won and succeeded in separating the North Russian army from the South Russian army, thus cutting off their vital petrol supplies, Hitler would win the war on the Eastern Front.

Soon after our arrival I met de Gaulle who, a few days later, invited my wife and me for lunch at The Connaught hotel where he took his midday meal nearly every day.

Soon after our arrival I met de Gaulle who, a few days later, invited my wife and me for lunch at The Connaught hotel where he took his midday meal nearly every day.

I remember, above all, the profound effect of finding myself for the first time in front of the man who represented France for us other Free French and for the huge majority of our country's friends throughout the world.

Fanny & François Charles-Roux were among a number of the Vlasto/Zarifi/Rodocanachi family to offer help to de Gaulle's Carlton Gardens HQ. Among these were their young cousin Helen Vlasto (1920-2001) (pictured right at Carlton Gardens) who had also answered the June 1940 'appel' to become an interpreter and receptionist, later joining the Royal Navy as a VAD nurse in Britain and then in Alexandria at the time of the Battle of Alamein.

By 1943 her brother Michael 'Pogy' Vlasto (1923-71) (pictured below right) had been seconded from the Royal Navy to become a liaison officer with de Gaulle in Dakar.

At about the same time their cousin Georges Zarifi made his escape through Pat Line across the Pyrenees to join the Free French forces in London.

At about the same time their cousin Georges Zarifi made his escape through Pat Line across the Pyrenees to join the Free French forces in London.

I didn't stay long at the Foreign Affairs commission. By the end of the year I was chosen to be the General's aide-de-camp, replacing Claude Serreulles who was soon to play a role at the highest level in France with the French Resistance. Thus I met the other aide-de-camp, Léo Teyssot who I quickly came to like and admire. And what can I say of Gaston Palewski, the General's chief secretary, who was our immediate boss? With limitless devotion he offered the General incomparable national and international political experience and to us others a kindness which won our admiration and affection for ever more.

Life in the large house in Carlton Gardens, the General's headquarters, was run on a protocol, as regulated as music off a piano-roll, which in its simplicity was fast-moving.

The General arrived at 9:00 from Hampstead [north London] where he lived in a large house with Mme de Gaulle and his two daughters, Elisabeth and Anne. After a salute from the official guard he would climb the stairs to a landing with doors leading to his own office, that of Gaston Palewski and the one used by the two aides-de-camps. The General's office and ours were two enormous, high-ceilinged rooms with French windows overlooking St James's Park.

The General received visitors and worked in his office until one o'clock. Then he would head for the Connaught Hotel by car, or on foot if it was fine, where he would lunch with a few guests, usually French and from either London or l'intérieur [France]. After lunch the General would return to his office to work and receive visitors until eight o'clock. Then he would return to Hampstead. Sometimes he held a dinner at the Carlton when he wanted to honour someone special.

The General received visitors and worked in his office until one o'clock. Then he would head for the Connaught Hotel by car, or on foot if it was fine, where he would lunch with a few guests, usually French and from either London or l'intérieur [France]. After lunch the General would return to his office to work and receive visitors until eight o'clock. Then he would return to Hampstead. Sometimes he held a dinner at the Carlton when he wanted to honour someone special.

Either Léo Teyssot or I would accompany him to the Connaught for lunch. Often, when on foot, passers-by would acknowledge him with respect and admiration. His personal success with ordinary English people was remarkable. Accompanying him to the Albert Hall for a ceremony, I saw people running to cheer Sir (sic) Winston Churchill who was in the car ahead. A small ovation greeted him as he got out, but it was clearly less strong and less warm than that which greeted the appearance of General de Gaulle.

Left: George Zarifi (1916-98) worked as a courier and guide helping Allied escapers and evaders in Occupied France on MI9's Pat Line, whose headquarters and safe house was in the Marseilles apartment of his uncle and aunt, George & Fanny Rodocanachi. When, in 1943, he faced serious risk of capture himself, he escaped from Marseilles to London along his own escape route across the Pyrenees and into Spain to join the Free French in London. His sister, Fanny Charles-Roux (née Zarifi), was the wife of the author of this memoir.

I had plenty of other opportunities to note this popularity with the English. The most striking happened at Barrow-in-Furness, in December 1942, on the occasion of a trip to this small industrial town to take delivery of a submarine built for the Forces Françaises Libres by Vickers Armstrong. It was raining in torrents and we were very late because of the weather. But, despite that, the whole population was in the street awaiting the General's arrival – and had been for several hours.

The ship-yard's director, who was with me in the car behind the General's, told me:

"This is one of the most socialist towns in England. I've never seen anything like this. I don't know who else these workers would have gone to so much trouble for in such numbers."

Later, while the General inspected the submarine, I was standing on the quay. Attracted by my uniform, the workers came to shake my hand, saying "Vive de Gaulle... Vive la France...", expressing their support and trust by any means they could.

This embodied the sort of support and trust – for those French who had refused defeat and had stood side by side with their allies – that de Gaulle commended to the eternal memory of the French people after the armistice.

Wartime Life in London

As everywhere in Europe, life in London was not easy during the war. Inevitably houses had little or no heating and we froze in our huge office at Carlton Gardens. It was more comfortable at home. Shortly after our arrival we had left my wife's uncle's [Michel Vlasto] partly burnt and icy house. His mother [Helen Vlasto née Zarifi] willingly lent us her apartment [in Porchester Terrace and later destroyed by a bomb]. There we were looked after by a former nanny of my wife's, the marvellous Jane, who was kindness and devotion personified.

As everywhere in Europe, life in London was not easy during the war. Inevitably houses had little or no heating and we froze in our huge office at Carlton Gardens. It was more comfortable at home. Shortly after our arrival we had left my wife's uncle's [Michel Vlasto] partly burnt and icy house. His mother [Helen Vlasto née Zarifi] willingly lent us her apartment [in Porchester Terrace and later destroyed by a bomb]. There we were looked after by a former nanny of my wife's, the marvellous Jane, who was kindness and devotion personified.

Above: General Charles de Gaulle inspecting members of the 'Corps Feminin' of the Forces Françaises Libres, London c. 1942. Courtesy of the Institut Charles de Gaulle.

She was helped by a typical London char lady, Mrs Dundas, who deserves mention. She was small, ageless and strangely dressed in a huge beret, a shapeless green overcoat and high laced boots. Mrs Dundas had all the chirpy spirit of a classic cockney. An avid reader of the News Of The World, she had a detailed knowledge of every crime and every perversion so assiduously displayed and then so piously condemned by this unique weekly newspaper.

Mrs Dundas was extraordinarily resourceful and loyal. After an attack of jaundice a doctor ordered me to eat only very light meat, ??? for example. She scoured London and found some [stringent rationing was in force].

Among the most irritating things was the 'black-out'. I remember groping around Belgrave Square trying to find a house where we had been invited for dinner. We had torches, of course, but it was forbidden to point them upwards to read the house numbers [for fear of attracting the attention of bombers overhead]. Another time, on a foggy night, while trying to get home from Paddington tube station, I got lost and, without realising it, entered the courtyard of a house where I then couldn't find my way out. Fortunately the occupants were worried by the sound of an intruder stumbling around and called the police who helped me home, just a few yards away.

Among the most irritating things was the 'black-out'. I remember groping around Belgrave Square trying to find a house where we had been invited for dinner. We had torches, of course, but it was forbidden to point them upwards to read the house numbers [for fear of attracting the attention of bombers overhead]. Another time, on a foggy night, while trying to get home from Paddington tube station, I got lost and, without realising it, entered the courtyard of a house where I then couldn't find my way out. Fortunately the occupants were worried by the sound of an intruder stumbling around and called the police who helped me home, just a few yards away.

Above: Britain's Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, inspecting 'blitz' damage in London.

Life didn't stop during the air-raids. There may have been less traffic but the traffic lights were just as scrupulously obeyed during the incredible barrages as at any other time. The sang-froid never faltered. I remember giving my secretary, who sometimes worked very late, a lift home in my office car. On the way an air-raid occurred and I suggested waiting at my house till it was over. She wouldn't hear of such a thing. Perhaps I had forgotten to mention that I was married and had a wife at home.

The Allied Invasion of North Africa

As M. Garreau had so accurately predicted, the Battle of Stalingrad marked the turning-point in the war and soon after the Allies passed from being defensive to offensive. This evolution was soon marked by the invasion of North Africa but demonstrated equally clearly Roosevelt's policy of alienating General de Gaulle. I remember how I came to hear of the selection of General Giraud [as commander of the French troops: de Gaulle's chief rival and a staunchly anti-Nazi, Free French leader]. It was my wife's grandmother [Helen Vlasto née Zarifi], a committed francophile, who gave me the news. It was her joy that made me realise the confusion that this choice was likely to create among our friends.

The same day, as the weather was quite good, I walked with General de Gaulle from Carlton Gardens for lunch at the Connaught. Passers-by recognised him, stopped him and congratulated him. Like our grandmother, they didn't yet understand that the Allies, by choosing to associate Giraud with the North African invasion rather than de Gaulle – their ally since June 1940 – had found a curious way in which to repay his loyalty – one which could only cause deep disarray in France. Scarcely aware of the congratulations the General muttered:

"Il y a bien de quoi!" [a deeply ironic 'Thank you!']

The Allies' behaviour became more and more deceitful. The assassination of Admiral Darlan came to clarify French opinions of their [Allied] policies. [The assassination of the pro-fascist Admiral who commanded and represented France in North Africa, was organised by SOE and carried out by a French national trained by SOE]

[Darlan was the fascist, pro-Vichy French admiral bidding for power in post-war France. Based in North Africa, he attempted to play the British off against their American allies and equally switched allegiance between Hitler, Vichy France and the Allies according to his interpretation of who would win the war. At a dangerous stage the US president Roosevelt failed to spot the duplicitous risk Darlan posed to the Allied North African campaign and lent him US support, despite warnings from both Churchill and Eisenhower. Had Darlan lived and mobilised the pro-Axis sympathies of the majority of the French, it is doubtful whether the 'liberation' of North Africa (1942-43) or the liberation of France and Europe (1944-45) could have succeeded. Eventually Churchill acted. Darlan was shot in the stomach, in his office, by a young Frenchman, Pierre Raynaud, trained by and working for SOE. He died soon after in hospital. Pierre Raynaud was executed, insisting to the end that he had acted on his own initiative. The assassination allowed de Gaulle to fill the vacuum in North Africa, build his power-base there and soon emerge as the putative post-war leader of France. It also exposed – not for the first time – American naiveté where European power-play was concerned and healed a potential rift between the USA and Britain.]

By chance it fell to me to inform the General of the assassination of Darlan. I was at the station to meet him on his return from a solo trip to Scotland. On my arrival the staff had surrounded me saying:

"How wonderful about Admiral Darlan!".

Realising that this referred to his assassination, I broke the news to the General as he got out of the train. Remaining perfectly calm he remarked:

"This is just the first." ["Ce n'est que le premier."]

I therefore assumed he was already aware of it, the assassination having taken place the night before. I later learnt that this wasn't the case and that he hadn't known about it.

Despite Roosevelt's desire to topple de Gaulle, his position in France and North Africa was too strong to be overturned. On 1 May 1943 we waited till night-fall before leaving for Algiers in a plane which took off secretly from an aerodrome in Cornwall.

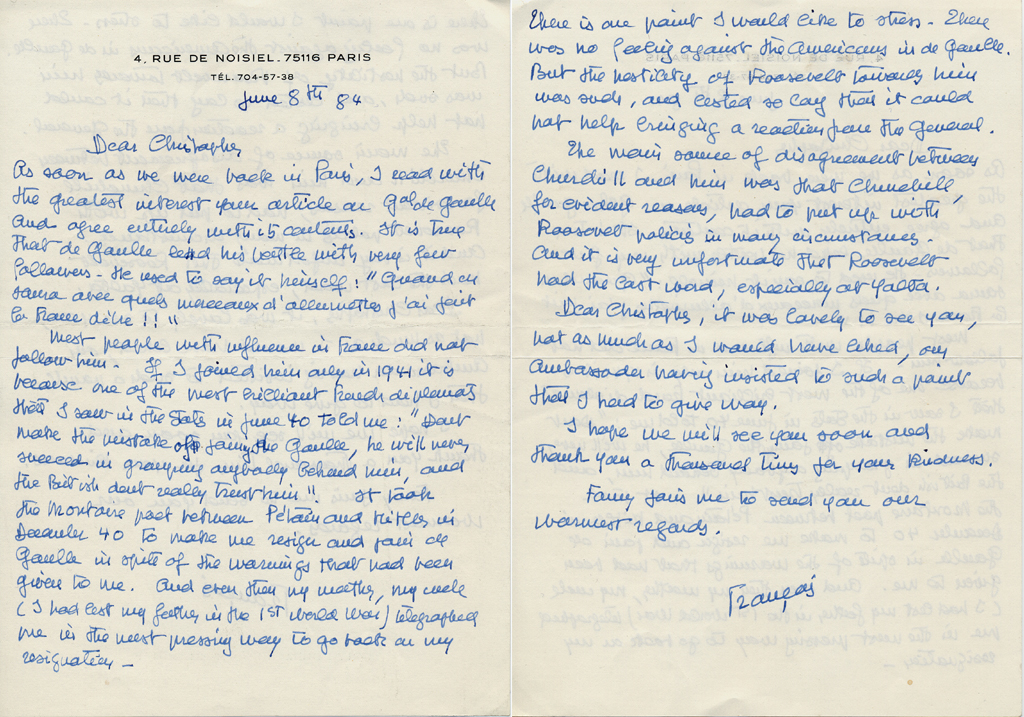

François Charles-Roux was prompted to write the above memoirs after reading an article on General Charles de Gaulle [London Portrait Magazine, June 1984 by Christopher Long] which was passed in turn to his friend Alain Peyrefitte. His immediate reaction to this article came, however, in a letter to the author as follows:

4 rue de Noisiel

75116

Paris

Tél: 704 57 38

June 8th 84

Dear Christopher,

As soon as we were back in Paris I read with the greatest interest your article on General de Gaulle and agree entirely with its contents. It is true that de Gaulle led his battle with very few followers. He used to say it himself: "Quand on saura avec quels morceaux d'allumettes j'ai fait la France dèlie!"

Most people with influence in France did not follow him. If I joined him only in 1941 it is because one of the most brilliant French diplomats that I saw in the States in June '40 told me: "Don't make the mistake of joining de Gaulle. He will never succeed in garnering anybody behind him, and the British don't really trust him." It took the Montaire pact between Pétain and Hitler in December '40 to make me resign and join de Gaulle in spite of the warnings that had been given to me. And even then my mother, my uncle (I had lost my father in the 1st World War) telegraphed me in the most pressing way to go back on my resignation. There is one point I would like to stress. There was no feeling against the Americans in de Gaulle. But the hostility of Roosevelt towards him was such, and lasted so long, that it could not help bringing a reaction from the General.

The main source of disagreement between Churchill and him was that Churchill for evident reasons had to put up with Roosevelt policies in many circumstances. And it is very unfortunate that Roosevelt had the last word, especially at Yalta.

Dear Christopher, it was lovely to see you, not as much as I would have liked, our Ambassador having insisted to such a point that I had to give way.

I hope we will see you soon and thank you a thousand times for your kindness.

Fanny joins me to send you our warmest regards.

François

After 1945, François Charles-Roux became a key figure in French foreign affairs and held a number of ambassadorships, including a crucial posting in Damascus.

Secret Papers: Escape & Evasion in Occupied France

Charles de Gaulle – The Man Who Stood Alone

© (1984) Christopher A. Long. Copyright, Syndication & All Rights Reserved Worldwide.

The text and graphical content of this and linked documents are the copyright of their author and or creator and site designer, Christopher Long, unless otherwise stated. No publication, reproduction or exploitation of this material may be made in any form prior to clear written agreement of terms with the author or his agents.