WHO ARE YOUR PEOPLE?

The Story of the Chiot & Phanariot Diaspora

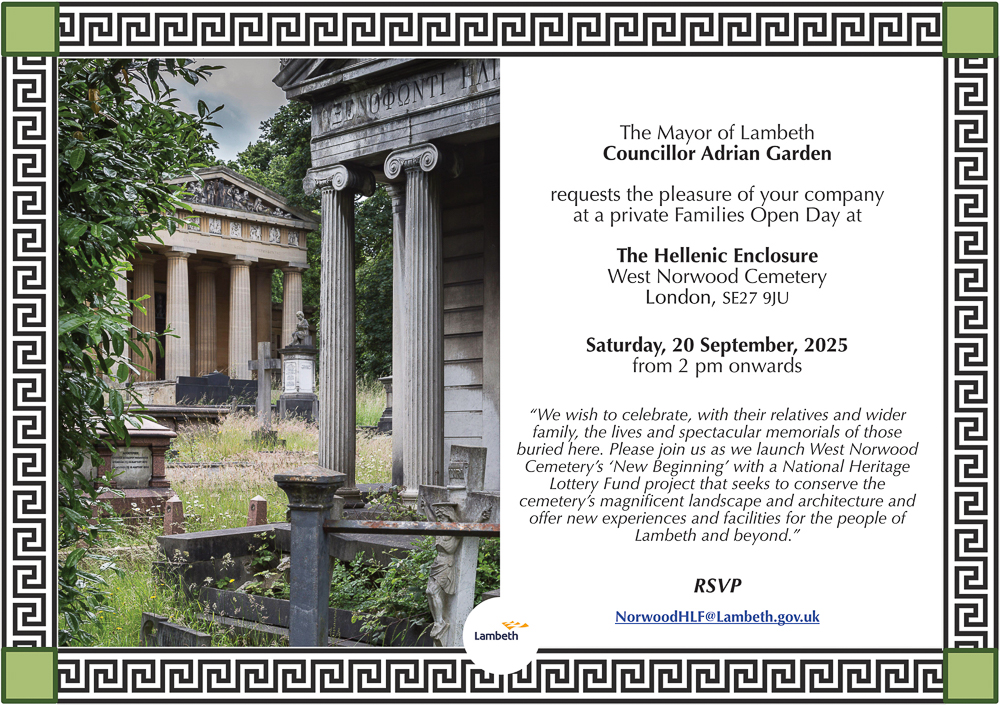

A talk by Christopher Long for an invited audience of descendants of the Chiot and Phanariot diaspora dispersed throughout Europe following the Massacres of Chios in 1822.

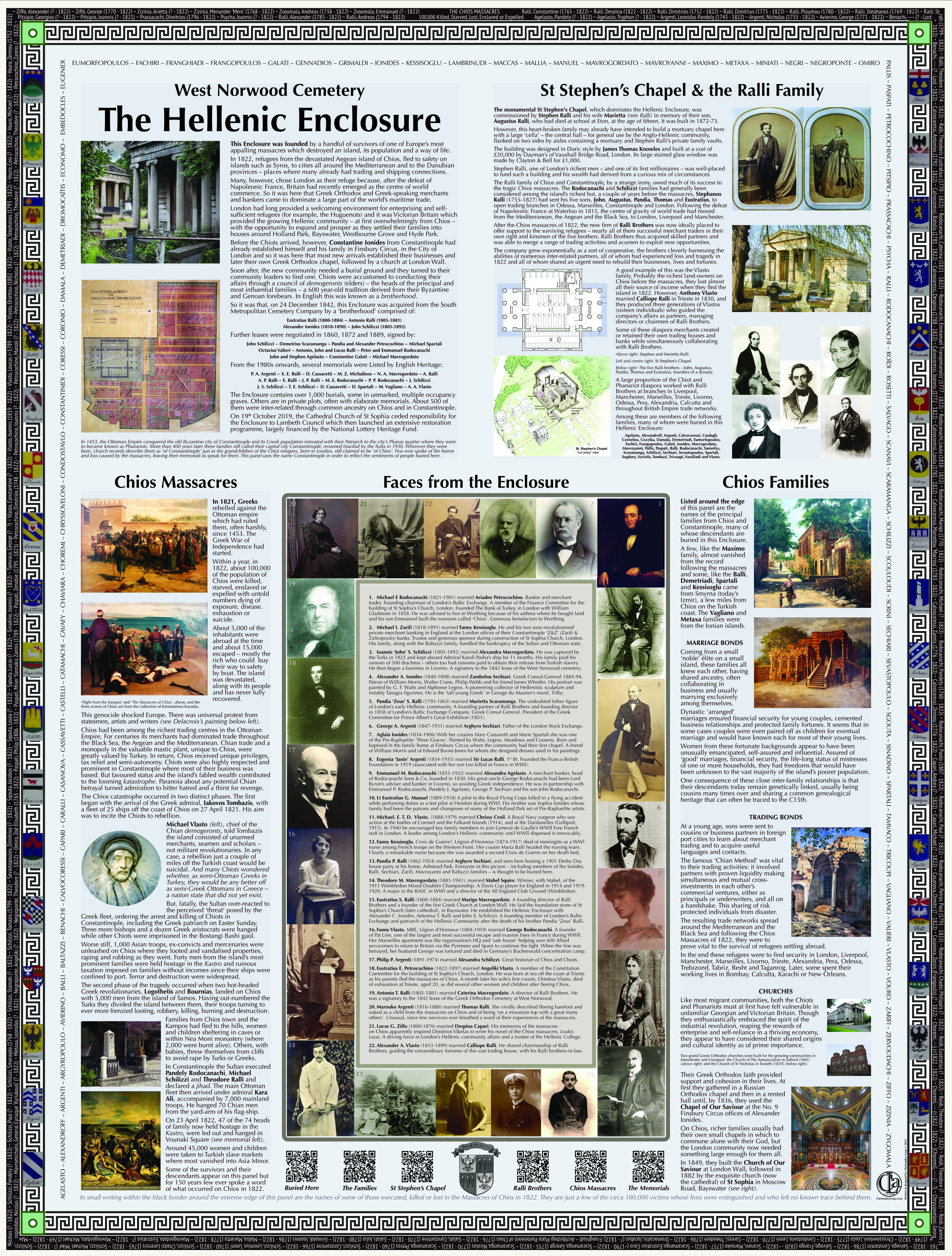

The Hellenic Enclosure, West Norwood Cemetery, London

20th September 2025

1. Forebears 2. Byzantines, Genoese & Ottomans 3. The Massacres of Chios 4. Survivors & Diaspora 5. Syros 6. Alexandria 7. Ralli Brothers 8. Livorno 9. Trieste 10. Marseilles 11. Liverpool & Manchester 12. London 13. Conclusion

It's an enormous pleasure to see you all here today. Thank you for helping to make this such a memorable occasion. I'm most grateful for those very kind words. In my turn I want to thank three people who have made today possible: my accomplice in crime, David Ralli, for his staunch cousinly support, the remarkable Kevin Crook at Lambeth Council and, above all, my wife Sarah who has patiently endured the presence of about 23,000 in-laws in her life. I've known a few of you since we were children. Many of us have come to know each other over the past thirty years or so. And some of you have kindly come to see us in Normandy. But many more of you I've never met before, although your names and sometimes your faces are very familiar. You and I are members of a select little group of about 1,700 living descendants of an inter-related Chiot and Phanariot diaspora, but, as the title almost asks: Who Are We?

INTRODUCING SOME FOREBEARS

MICHAEL VLASTO 1762-1849 m. Alexandra Caralli

One of the earliest portraits we have of a Chios nobleman. He was a considerable landowner and the island's chief demogeront in 1822.

Let me start with Michael Vlasto. He's an uncle, a grandfather or a cousin to almost all of you, as are most of the people we'll be meeting this evening. This is because they routinely married cousins within a small group of families. They'd done it for centuries.

So, almost all of us here are related to each other as cousins, and usually many times over and we share a huge amount of DNA. But more interestingly, we share a story which I'll try to tell you briefly and which involves a great tragedy.

THE ISLAND OF CHIOS, JUST OFF THE COAST OF TURKEY

Michael Vlasto was born in 1762 on the island of Chios, just off the Turkish coast, and he died in 1849 as a refugee in Trieste. He was descended from Rodocanachis, Rallis, Argentis, Maximos, Petrocochinos and, of course, his own Vlasto family.

But significantly for us today, his 11 children married two Mavrogordatos, one Paspati, two Petrocochinos, three Rodocanachis, one Vouro and, thank the Lord, an entirely unrelated grand-daughter of General Josef Dwernicki, a Polish count.

Among the most prosperous families on Chios were the Rodocanachis and Schilizzis, with Argentis, Petrocochinos and Scaramangas close behind, but Michael and his Vlasto brothers were probably the largest property owners on the island. And crucially, in 1822, Michael was the chief demogeront, that's to say the leader of the Greek community's council of elders.

He's among the first people I know for whom we have a life-like portrait. As you can see, he's old and he's lived a lot. He has world-weary eyes beneath the characteristic high-domed hat of a patrician, Greek Orthodox Ottoman. The sculpture is no doubt derived from a painted portrait, now lost.

MICHAEL VLASTO 1762-1849 m. Alexandra Caralli

The author with his great-great-great grandfather who was buried in Trieste alongside many of his large family.

I first discovered it on Michael's tomb in Trieste in 1999 when I was a rather bruised war correspondent reporting the very nasty ex-Yugoslavian Balkan wars of the 1990s.

Taking a few days' break, I found myself in front of a three times great-grandfather, who, 175 years earlier, had experienced similar atrocities to those I was witnessing in nearby Bosnia-Hercegovina.

Now I'm going to introduce you quite rapidly to eight members of the Schilizzi family in order to set the scene for the rest of this talk.

Chadzi ZANNIS SCHILIZZI 1720-1800 m. Franga Avierino.

This is one of a number of cameo portraits commissioned in the mid-C20th by Philip Argenti to depict some of his ancestors. It's unclear how many of them were derived from original portraits of the sitters and how much comes from the imagination of the artist. They are displayed at the Koraïs Museum, on Chios.

This is Zannis Schilizzi. His costume is authentic for the late 18th century, but the picture was painted in the 20th century, possibly working from a reliable original. And these reproductions were necessary.

Those sumptuous Genoan-Ottoman mansions on Chios, their libraries crammed with polyglot books, paintings, vivid textiles and fine furniture were, by all accounts, temples to the Renaissance. But, when they were pillaged and burnt in 1822, almost nothing was left. We have only the accounts of travel writers of the period, along with Philip Argenti's attempts to 'create an impression'.

FRANGA AVIERINO 1738-1806 m. Zannis Schilizzi

And this is Zannis's wife, Franga Avierino, though, as with all these cameos, the background is kitsch and very 20th century.

Chadzi STEPHANIS SCHILIZZI 1757-1820 m. Hypatia Calvocoressi

We might say the same for Zannis's son, Stephanis. His hat and costume suggest he is a high-ranking Greek Orthodox merchant or Ottoman administrator. You just have to ignore the folksy Chios windmill.

ZANNIS 'JOHN' STEPHANOVIC SCHILIZZI 1806-1886 m. Eleni Vouro

He was captured by the Turks in Mesta on 18 April 1822 and held hostage until he was found in Smyrna by a Stephen Vernatsa who paid his ransom. He fled Smyrna for Trieste, then Livorno and finally Constantinople. He became an immensely successful magnate in Constantinople with three sons who ended up in London. He Russified his name for business purposes and bought a plot in the Hellenic enclosure.

Now let's meet Stephanis's son, John Schilizzi. He was a 16 year-old at the time of the massacres of Chios and held hostage in Smyrna until a hefty ransom was paid by a well-wisher. He was to become a magnate in Constantinople and had three sons who ended up in London...

JOHN SCHILIZZI 1840-1908 m. Virginia Sechiari

Buried at the Hellenic Enclosure, West Norwood Cemetery.

... one of these being this John Schilizzi, who is buried here in the Hellenic Enclosure and whose tomb was listed by English Heritage. And John had a son...

STEPHEN SCHILIZZI, JP 1872-1961 m. Julia Ralli

An English land owner, a JP, High Sheriff of Northampton and president of Kettering Conservative Party.

... called Stephen, a pillar of the British establishment, who spent the last third of his life at Loddington Hall, a 13th century house which, by 2024 had, rather inevitably, been turned into 12 luxury apartments.

JOHN SCHILIZZI 1896-1985 m. Lady Gabrielle Waldegrave

Captain in the Northamptonshire Yeomanry and attached to the 6th Dragoon Guards on the Western Front in WWl.

And so it goes on because Stephen too had a son, John Schilizzi who, on leaving Harrow, served as an officer on the Western Front in WWl.

STEPHEN SCHILIZZI b. 1937 m. Diana Allfrey

Principal trustee of the Schilizzi Foundation, an educational charity founded in memory of his great aunt Helena Schilizzi and her husband Eleftherios Venizelos.

And there I want to leave the Schilizzis in peace, except to say that of course there's another generation, one of whose number is with us this evening in the shape of Stephen Schillizi. Welcome, Stephen!

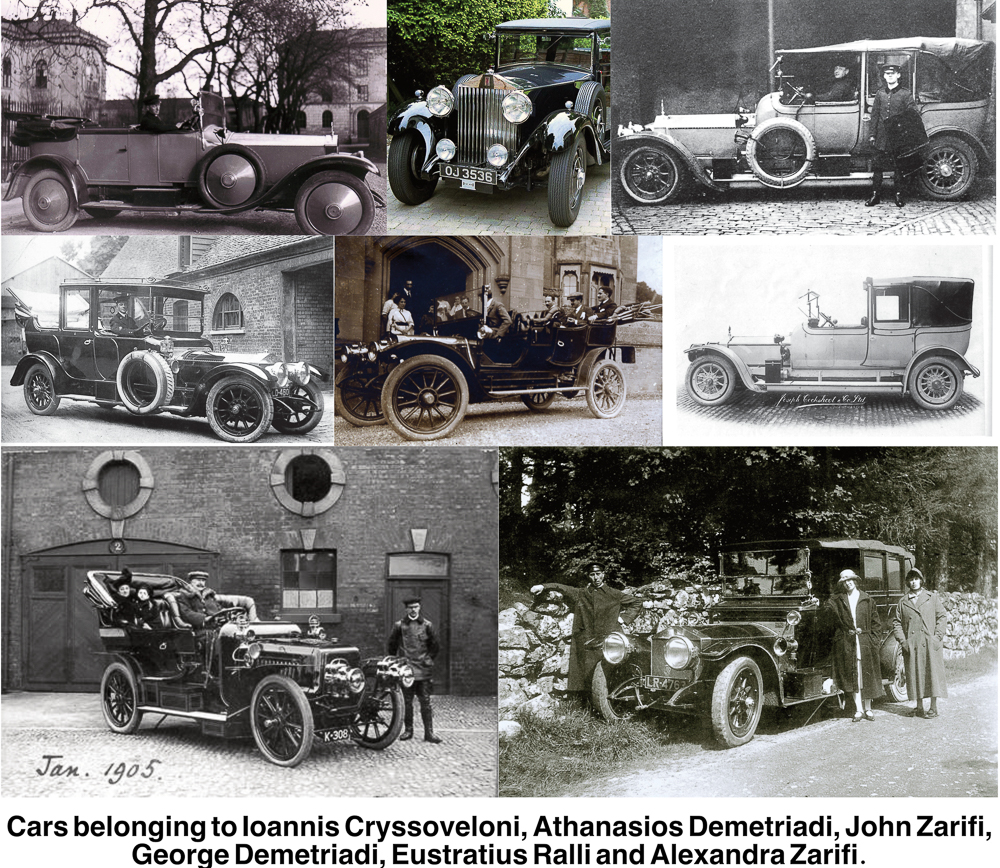

RALLI BROTHERS, INDIA (1894)

Directors and their wives from the following families: Ralli, Vlasto, Scaramanga, Rodocanachi, Frangopoulos, Schilizzi, Cornelios, Fachiri, Mavrogordato and Condostavlo.

So, how and why did our 'exotic' Byzantine-Genoan-Ottoman-Greek families, after centuries of generally peaceful existence on Chios and in Constantinople, suddenly find themselves thrown across the seas, most of them washing up in England, France, Italy, Egypt or the USA. How did they transform from Ottoman grandees to largely upright Victorian and Edwardian ladies and gentlemen, ultimately ending their days in Lambeth's Hellenic Enclosure?

What was the voyage between 18th century Michael Vlasto...

Dr MICHAEL VLASTO 1888-1979 m. Christian Croil

Son of a Phanariot Greek mother and a Chiot Greek father, he was born in Paris, educated at Winchester and became a surgeon in London before serving in the Royal Navy in WWl. In WWll he successfully encouraged two of his children to work for General de Gaulle's 'Free French' movement and several of his cousins to fill key roles in de Gaulle's wartime administration at Carlton Gardens in London.

... and my much-loved 20th century grandfather, another Michael Vlasto?

BYZANTINES, GENOESE AND OTTOMANS

BYZANTINE EMPIRE EXPANSION

The dark green shows the extent of the Byzantine Empire in AD 527. The light green areas show the territorial gains during the reign of Justinian who died in AD 565.

As you know, all our families have roots somewhere in the old Byzantine empire. But the first pivotal moment in their story occurred, I think, in the 14th and 15th centuries when the Genoans entered the scene. After 1,000 years, the vast Byzantine empire had shrunk to become little more than the city of Constantinople itself.

14th CENTURY GENOAN AND VENICE ACQUISITIONS

Genoa and Venice acquired key islands in the Aegean Sea and off the Ionian coast. In particular, Genoa had trading colonies on Chios, Lesbos and at Galata in Constantinople.

The dying giant had lost its territories to invaders and in 1453, the Turkish Ottomans were about capture Constantinople and rebuild an equally vast empire of their own. But shortly before this happened, in the 1300s, Genoa had created trading colonies on islands such as Chios and, most significantly, had a large merchant colony at Galata, just across the Golden Horn from the great city itself and beside its principal port at Pera.

OTTOMAN CONSTANTINOPLE

Across the Golden Horn (to the right) lies Galata where trade partnerships led to marriages and dynasties between Catholic Genoans and Orthodox Greeks.

Over the following centuries Greek merchants based in Constantinople formed alliances with Genoan merchants based in Galata. These business alliances were underwritten by marriages between Greek Orthodox and Roman Catholic families.

GREEKS GENOAN NAMES

Real marriages can be detected in the double-barrelled names derived from both Greek and Latin roots. Names in Italic are Genoan and those in bold are Greek.

You can see it in the names of many our families, some of which are of Genoan origin, like Argenti and Salvago, and some of which are double-barrelled, like Calvocoressi and Mavrogordato, the first part being Genoan and the second part Greek. It is also interesting that most of the Genoan families who intermarried with Greeks fairly quickly converted to Greek Orthodoxy and became Greek-speaking.

A GREEK ORTHODOX MARRIAGE

Orthodox Greeks from the Phanar or Galata quarters of Constantinople formed trading partnerships, leading to marriages, with Roman Catholic Genoans in their colony of Galata, although this in fact is a purely Phanariot marriage.

This is why Greek-Genoan merchants came to dominate the shipment of grain and other commodities from the Black Sea to feed and supply the growing Ottoman empire from the 15th century onwards. And note that this is an unusual group of pragmatic families, happy to marry across religious boundaries in pursuit of peace and prosperity, but perhaps setting themselves apart from mainstream Greek thinking. In any event this explains the Genoan blood that runs through most of us.

OTTOMAN CONSTANTINOPLE

Viewed from the Galata quarter across the Golden Horn waterway.

So now we leave Constantinople and head for Chios, an island that early travel writers considered paradise on earth.

THE PORT OF CHIOS IN 1700

The Kastro (fortress) sits to the right of the harbour with a smaller fort on the opposite side. There's a monastery at the extreme left, mosques in the Chora (town centre) and lighthouses on each side of the port entrance. This happens to be one of the most accurate maps we have of this period.

As in Constantinople, so on Chios. The island was also a Genoese trading colony, controlled by a sort of joint-stock trading company known as the maona.

CHIOS IN 1782 WITH THE KASTRO & CHORA

An Orthodox church sits comfortably beside the minaret of an Islamic mosque, just as the famously pragmatic Orthodox Chiots were happy to marry their daughters to Catholic Genoans in pursuit of peace and prosperity. Famously – even shockingly in the eyes of many Greeks – they shared church facilities with Latin masses sung in Orthodox churches. Some Negroponte families, for example, remained Catholic.

Inevitably the Genoese must have worked hand-in-hand with the indigenous population of Hellenic merchant traders, resulting in similar commercial partnerships and family marriages. Indeed the more successful families must have run their businesses out of both Pera and Chios simultaneously. This image from 1782 – just 40 years before the massacres – shows a harmonious cluster of mosques beside an Orthodox church. Ever pragmatic, Orthodox Chiots sometimes permitted Catholic masses in their churches, which shocked many Greeks elsewhere.

OTTOMAN GOLD COINS MINTED ON CHIOS DATED 1603

Gold was the measure of wealth in a golden age for Greek-Genoese merchants in Constantinople and on the island of Chios.

And perhaps Chios had already become the delightful island on which you brought up your children, spent your summer holidays and lived out your declining years surrounded by your grandchildren. Certainly the island was renowned for its schools, so this was where you were educated.

A GREEK LADY OF CHIOS IN THE LATE 18th CENTURY

In an age before nations, head-dress and costume immediately described your origin, occupation, culture, religion and status.

And it's this point that I'd like to say that not all my images are directly relevant to what I'm saying. Sometimes, like this one, they're just background scene-setting.

A GREEK LADY OF CHIOS OF THE C17th CENTURY

Dressed in C17th style, she would have looked antique to those who were about to face the Chios Massacres in 1822. But she would have been instantly recognisable in the 1600s as a Greek Orthodox, Greek-speaking, Ottoman noble woman.

You and I describe ourselves as British or French, our passport being perhaps our most valuable possession. But our Chios forebears lived in an age of city states not nation states. There were no coloured maps, no rigid frontiers and no passport controls. Eighteenth century people defined themselves by their home city, their occupation, their mother-tongue and their religion. And all of these were reflected in specific headdress and clothing, both for men and women, that made them instantly recognisable.

CHIOS PORT AND KASTRO IN 1782

A view of the coast from the port town of Chios and Kastro of Chios (left), looking north towards Vrontardo in the distance (right).

To understand how they were blind-sided by the massacres, we have to accept that for centuries these people had been sublimely at home wherever they happened to be, polyglot merchants and mariners, masters in their own world, freely roving the world's trade networks until they were caught unawares by the rise of 19th century nationalism.

THE MASSACRES OF CHIOS

So now we come to the distressing story of the Massacres of Chios. It's a bit grim but it directly concerns us. Our families were all marked by it and most of us were unable to commemorate its 200th anniversary in 2022.

CHIOS: ITS PORT AND KASTRO IN CIRCA 1650

The background is that, on 25th March 1821, Greeks in Moldavia and Wallachia (present day Romania) rebelled against the Ottoman empire which had ruled them, often harshly, since 1453.

PRINCE ALEXANDER MAVROCORDATO 1791-1865 m. Chariclea Argyropoulo

A cousin of the Mavrogordatos of Chios, he grew up in the Ottoman Danubian provinces (present day Romania) where families such as his ruled as princes on behalf of the Sultan. He was one of the leaders of the Greek War of Independence and became the first president of the newly created Greek state in 1828.

This was the start of the Greek War of Independence, master-minded by a secret Russian-backed society known as the Philiki Heteriae and it was led by some of the Greek Phanariots we met in the Phanar. These first rebels were princes, ruling the provinces of Moldavia and Wallachia on behalf of the Sultan, and among them was Prince Alexander Mavrocordato, a cousin who was eventually to become the first president of Greece.

SULTAN MAHMUD ll 1785-1839

The Ottomans soon dealt with that first revolt but the Sultan's furious reaction was a foretaste of things to come. He hanged the entirely innocent Patriarch of Constantinople, Gregorius V, on Easter Sunday and with him three bishops, several eminent clerics and a dozen Greek aristocrats in the Ottoman government.

THE BATTLE OF NAVARINO 20 October 1827

National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London (Caird Fund)

Then began six years of bloody fighting between Turks and Greeks until, in 1827, Britain, France and Russia, acting decisively at the Battle of Navarino, ensured a declaration of Greek independence in 1828.

And while it all sounds rather glorious, it was, as you know, much less glorious on the island of Chios in 1821 and 1822.

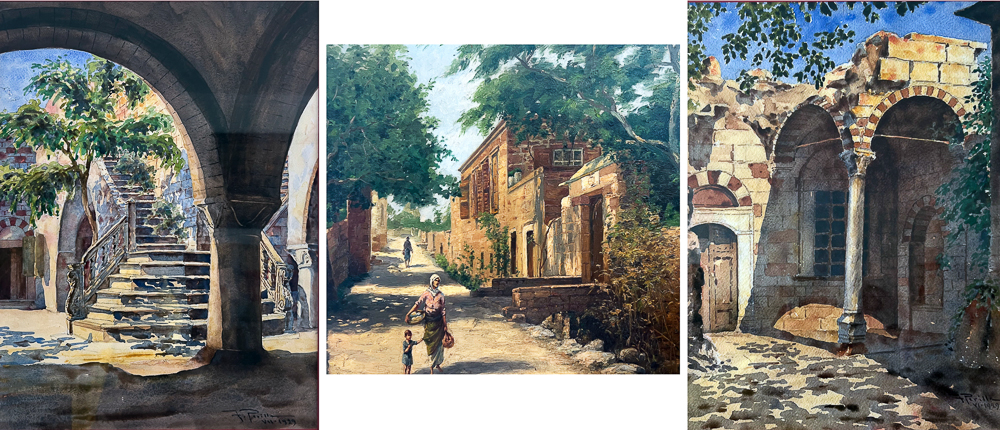

THE KAMPOS, CHIOS

Paradise on earth before 1821

In Spring of 1821, the population of Chios had been about 120,000. A year later, about 100,000 (83 per cent) had been killed, starved, enslaved or expelled. Untold numbers had died of exposure, disease, exhaustion or suicide and 43,000 had simply vanished into the slave markets of Asia Minor, never to be seen again.

About 15,000 escaped in rescue boats and about 5,000 happened to be abroad at the time – sailors, migrant workers and some of our merchant forebears. Those who escaped were mostly those who could afford to buy their way to safety. The devastated island has never really recovered but you and I are the consequence of the 17 per cent of the population who made it to freedom.

GREEK FAMILIES AWAITING DEATH OR SLAVERY

by Eugène Delacroix (Le Louvre, Paris)

This genocide shocked Europe, provoking universal protest from statesmen, writers and artists – especially in France and Britain – among them Eugène Delacroix.

Tragically the katastrophi was largely the consequence of Chian success. As we've seen, Chian merchants were the golden geese of successive Sultans, feeding and supplying their growing empire. They had been rewarded with unique privileges, tax relief and much autonomy on their lovely island.

But favoured status and fabled wealth led directly to disaster. At the very suggestion of Chian betrayal, the Sultan's admiration turned to hatred and revenge.

As we shall see, the Chios massacres occurred in three distinct phases and each began with the arrival of a fleet off the Chian coast.

CHIOS PORT AND THE KASTRO

This image, dated 1690, clearly shows the channel which once separated the Aplotaria and Chora town centre (left of centre) from the heavily fortified Kastro (right of centre). Today this moat has disappeared but the promenade along which the hostages were to be hanged in April 1822 (later named Vounaki Square) is clearly visible. The C11th monastery of Nea Moni is seen nestling among the mountains.

Phase 1: A Greek Fleet Arrives

The first fleet arrived on 27 April 1821 when a Greek admiral, Jakobos Tombazis, anchored twenty-five ships at Vrontado, just north of Chios town. He sent messengers to the island's leaders – the demogeronts – urging them to join the Greek rebellion.

Michael Vlasto, the chief demogeront we met at the start of this talk, told Tombazis that the island was not oppressed, consisting of unarmed merchants, seamen and scholars – not militant revolutionaries.

THE ISLAND OF CHIOS, JUST OFF THE COAST OF TURKEY

South-east is the island of Samos and north-west is the tiny island of Psara.

Furthermore, he explained, rebellion a couple of miles off the Turkish coast would be suicidal. He might also have said, but probably didn't, that most Chiots wondered whether, as semi-Ottoman Greeks in Turkey, they would be any better off as semi-Greek Ottomans in a future Greece. Tombazis stayed for six days and left a thousand rifles and ammunition in return for five head of cattle.

THE KASTRO AT THE NORTHERN END OF THE CHIOS PORT

In 1821, this former Byzantine fortress was the headquarters and residence of the island's governor, Bachet Pasha. It was here that 74 of the island's nobility were to be held hostage for almost exactly a year.

Constantinople immediately demanded that forty self-selected hostages from among the island's nobility be held as hostages in a room within the Turkish governor's castle, the Kastro.

The next day Michael Vlasto met Bachet Pasha who was embarrassed to be treating old friends in this way. For a bribe, he agreed that the first forty hostages could be replaced by another forty at the end of each month. These men, mostly heads of the principal noble families, were fed and clothed by their families and hired a small coffee shop in the garden for 50 piastres a month.

There was an uneasy stalemate during the winter of 1821 as the Turks reinforced the Kastro with forced labour. Inevitably, the hostage situation and the murder of senior family members in Constantinople had irreparably damaged the previously excellent relationship between Turks and Chiots.

ENTRANCE GATE TO THE SUBLIME PORTE, CONSTANTINOPLE

The Sultan's court and seat of Ottoman power and diplomacy.

Then, on 20 December 1821, Francis Werry, British consul in Smyrna, warned Britain's ambassador in Constantinople and Bachet Pasha on Chios that the nearby island of Samos was preparing to invade Chios with three thousand Greek revolutionaries.

Lord Strangford, British ambassador in Constantinople, was assured by the Ottoman Porte that Chiots were regarded favourably and represented no threat to its interests.

CONSTANTINOPLE: THE SEVEN TOWERS

And yet, almost immediately, a large number of Chiots in Constantinople were rounded up and imprisoned in the Bostandgi Bashi gaol. Almost all of them were to be garrotted, hanged or beheaded a few months later.

A Chian merchant, Alexander Dimitrios Ralli [1780-1858], on his way back from business in India, was asked by the provisional Greek government to assess the mood on the island. He reported that there was little enthusiasm for rebellion and so any idea of military support for Chios was abandoned.

THE KASTRO, CHIOS

The northern side of the now severely damaged Turkish garrison.

Next, the Ottomans dispatched one thousand assorted Asians, ex-convicts and mercenaries – under no leadership – to reinforce the Chios garrison and these reinforcements soon set about plundering the town, breaking into houses and attacking, raping and robbing the inhabitants.

Huge taxes were imposed to pay for these troops. Law and order broke down and food supplies were cut off. Much of the populace headed for the hills, while those who returned found their homes had been looted and vandalised.

THE KASTRO, CHIOS

Remains of tower on the northern side of the Turkish garrison.

It was now that three of the island's most prominent citizens, Pandely Rodocanachi, Michael Schilizzi and Theodore Ralli were arrested and taken to Constantinople's Bostandgi Bashi gaol, transported overland for fear of Greek attempts at a naval rescue.

With Chian shipping confined to port, there was no trade, no income and no one could escape. Morale sank and conditions deteriorated everywhere. Two of the hostages in the Kastro died – Matthew Psiachi and Theodore Petrocochino. Into this abyss sailed a man called Logothetis.

LYKOURGOS LOGOTHETIS 1772-1850

The self-styled commander of the island of Samos, he launched a catastrophic invasion of Chios. His ill-disciplined Greek 'troops' caused huge destruction and misery among the very people he claimed to be liberating.

Phase 2: A Samian Fleet Arrives

It was on 11 March 1822, that the second fleet arrived and the second phase of the Chios catastrophe began. Lykurgos Logothetis, was a hot-headed revolutionary and de facto commander of Samos, an island due south of Chios.

THE ISLAND OF SAMOS, SOUTH-EAST OF CHIOS

Logothetis's Greek-Samian fleet of sixteen ships dropped anchor at Karfas Bay in the south-east of the island. He fired a few long range shots and landed around two thousand troops, later augmented to four or five thousand.

The Samians were welcomed by a few villagers until their head-man's authority was challenged and he was killed. The troops then advanced on Chios town demanding Turkish surrender.

Batchet Pasha responded by calling in more hostages from among the island's leading families who were now incarcerated in an appalling dungeon in the heart of the Kastro.

PERIVOLI, KAMPOS, CHIOS

The former home of the Caralli family who fled Chios for Syros in 1822.

The situation became pitiful. The Turks, were effectively besieged in their Kastro, relying on foreign consuls for information and being bombarded by ships at sea and 5lb cannon on land.

A VLASTO ESTATE AT 'LITSAKI'

The Vlastos had as many as twelve properties in the Kampos and four more in Chios town, two of which survive today. Many were badly rebuilt after the devastating earthquake on Chios on 3 April 1881 (7.3 Richter) which caused 7,866 casualties, destroying most of the island's remaining buildings.

Meanwhile, Logothetis deposed the demogeronts, on whose support he'd been counting, and fell out with a fellow commander.

His armed men, now out of control, set about killing Turks, setting fire to the customs house as well as town houses and warehouses along the waterfront. Anything of value was shipped away on the Chian vessels the Turks had confined to port.

AN ARGENTI ESTATE ' THE ARGENTIKON' IN THE KAMPOS

This picture from the mid-C20th represents the villa with its Argenti owners as it might have looked before 1822. The house was lavishly restored by Philip Argenti after WWll, although it apparently belonged to his cousin, the archimandrite Cyrille Argenti, Orthodox archbishop in Marseilles. Courtesy of Constantinos Kavadas

The former demogeronts and other leading families now abandoned the Chora (the town centre) and headed for their country estates in the Kampos, a couple of miles to the south.

FLIGHT FROM THE KAMPOS

One of several paintings commissioned by Philip Argenti showing scenes of Chios, two of which depict the effects of the 1822 Samian and Turkish invasions of the island. In this painting the walled estate is typical of the scores of family villa properties in the Kampos and the costumes and appearance of the nobleman, his family and their servants, seems authentic. Courtesy of Constantinos Kavadas

By now large numbers were heading into the hills, hiding in caves and living off the land, the sea-shore and rock-pools. The richer families, with more to lose, may have hoped to hold out in their country properties, with loyal servants and estate workers beside them.

THE MASSACRES OF CHIOS

A painting commissioned by Philip Argenti depicts Greek victims of the Turks trying to escape from the west coast of the island. The scene takes place on high ground with a burning village to the right. The nobleman with the high-domed hat seems to be the same person shown leading his family's exodus in Flight From The Kampos. (Courtesy of Constantinos Kavadas)

Already some desperate refugees were being plucked from the western beaches by Greek boats from the neighbouring island of Psara.

It was now April and Sultan Mahmoud ll, enraged by the 'Greek rebellion' on Chios, ordered the execution of some of the Chian hostages in Constantinople.

He then ordered the main Turkish fleet to set sail for Chios on 5th April 1822. They were to be joined by some 15,000 crack troops from Asia-Minor.

GATEWAY TO THE CALVOCORESSI ESTATE IN THE KAMPOS.

The scores of Kampos estates each had a set of characteristic elements: a distinctive and dominant main gateway, a vine-trellised courtyard, a large donkey-powered well and a series of water basins, cisterns and irrigation channels. On the ground floor of the villa were service and storage areas for workers and produce. On upper floors were the family's private rooms, nearly always associated with a large first-floor terrace with views across the Kampos. Surrounding the villa, the land produced oranges, lemons, mulberries and fruit and vegetables of all sorts. This harvest provided owners with an important secondary income and employment for numerous estate workers and servants.

On 11th April, Mr Calvocoressi asked his estate-keeper to prepare mules to carry away valuables to his house in the Kampos, where, from an upper floor, he peered through binoculars to see the Turkish fleet in full sail led by Capitan-Pasha Kara Ali's flagship, Victory, accompanied by twenty-four ships.

THE CALVOCORESSI ESTATE IN THE KAMPOS

It may have been on the site of this house (rebuilt after the 1881 earthquake) that Mr Calvocoressi, armed with binoculars, watched the arrival of Capitan-Pasha Kara-Ali's Turkish fleet. Was this Zannis Calvocoressi (1776-1822 m. Battou) who died or was killed at about this time? Other candidates are his brothers Constantine (1778-1841) and Petros (1774-1830), both of whom survived the massacres.

Phase 3: A Turkish Fleet Arrives

This was the third fleet to arrive and the start of the most deadly phase of the catastrophe. Some ships dropped anchor in Chios harbour and bombarded the town which has never recovered its former elegance.

Meanwhile the Greek-Samian fleet sailed away, abandoning its land forces and their leader, Logothetis, who headed for the west coast at Elindas, killed his Turkish prisoners and then sailed home to Samos.

His now-leaderless Samian troops, however, refused to surrender and many hungry Chiots – with most of their leaders held hostage – now joined the Samian horde.

And it was this news, when passed to Constantinople, that led to the Sultan's decision to kill the hostages in the Kastro.

A CHIOS VILLA AND GARDEN IN THE KAMPOS IN 1776

Note the villa to the left with its characteristic water-wheel and marble cistern. The rather dilapidated state of the place is more caracteristic of C18th artistic fantasy than the reality of highly efficient horticultural businesses.

On 12th April, 7,000 Turkish troops from Smyrna landed and dispersed through the south of the island, killing and destroying as they went. Their orders, amounting to a jihad against infidel Christians, included re-taking the island, eliminating males over twelve, all women over 40 and infants. Surviving women and children were to be enslaved. Then they were to lay waste to the island.

THE C11th BYZANTINE MONASTERY OF NEA MONI

Now a World Heritage site, this jewel on the ravaged island of Chios survived the massacre and the fires that burned hundreds of refugees who sought refuge here in 1822. It was again much damaged by the 1881 earthquake.

Around 2,000 women with children and priests sought sanctuary within the 11th century Byzantine monastery of Nea Moni. Eventually the doors burst open and the building was set on fire. None survived. Many of their skulls are displayed there to this day.

ANAVATOS

Thousands of refugees fled into the mountains and to hilltop villages like Anavatos. Here women are said to have jumped from the cliffs, with babies in their arms, to avoid rape and disgrace at the hands of the Turkish troops.

Some women, with infants in their arms, chose to jump from cliffs such as these at Anavatos, while other refugees flocked to Aghios Georgios, Mesta and the harbour at Pasha Limani, hoping to be picked up by boats from the neighbouring island of Psara.

A HARBOUR IN NORTHERN CHIOS

The people of Psara offered extraordinary support to the Chian refugees, rescuing them by boat and sheltering them until they could be moved on. The tiny island's population of 7,500 swelled to 23,000. This further enraged the Sultan and on 20th June a Turkish reprisal force arrived. Around 17,500 were killed or taken into slavery.

It seems that at least eight large vessels were sent to pick up refugees – free of charge – from the northern coast.

MAROUKO ARGENTI 1816-1880 m. Thomas Ralli

She remembered fleeing naked to a mountain top with many others. Her usual clothes would have attracted attention from Turks looking for children of the rich and opportunities to earn small fortunes in ransoms. Naked she was valueless.

Among these was Marouko Argenti, one of the few survivors ever to speak of the massacres. She had vivid memories of fleeing barefoot and naked as a six year-old and of being on a mountain top with a great many others. Had she been wearing her normal high-status clothing, she would have drawn immediate attention to her value as a hostage for ransom. Naked she appeared valueless.

SAINT MINAS MONASTERY

Constantine Choremi (1796-1878 m. Perdica) fled here with his wife and two children who were captured by the Turks. He never saw them again. He then hid in tombs with abandoned children for many days and was white-haired by the age of thirty. He yearned to die on a Good Friday and duly did so.

Similarly, Constantine Choremi fled with his wife Perdica and two children towards the monastery of St Minas. He survived but she and the children were captured by Turks and never seen again.

On 25 April 1822, Viscount Strangford wrote to London: "... We have got rid of all our ruffians, who have gone to partake in the plunder of Scio..."

THE MASTIC VILLAGES

Diplomats persuaded Bachet Pasha to offer an amnesty to people from some of the mastic villages. When they gave themselves up, the Turkish commander, Helas-Oga, was as appalled as the diplomats when the Pasha gave orders to kill them: "Innocent or guilty, all are to die, such is my wish". The first seventy to come forward were hanged from the yard-arm of the Turkish admiral's flagship in Chios port.

With shocking cynicism, the hostages in the Kastro were now offered their freedom in return for two million piastres, payable in cash immediately. Under the circumstances this was impossible to arrange, as the Pasha surely knew. And in any case he had already received the Sultan's orders to execute them.

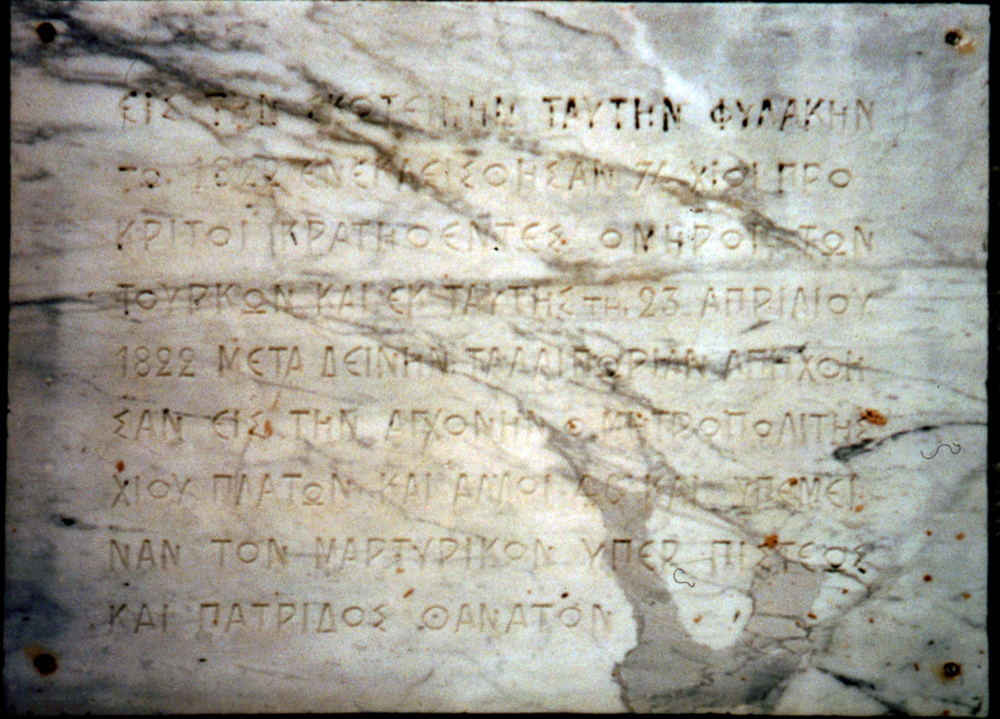

A PLAQUE BESIDE THE KASTRO DUNGEON DOOR:

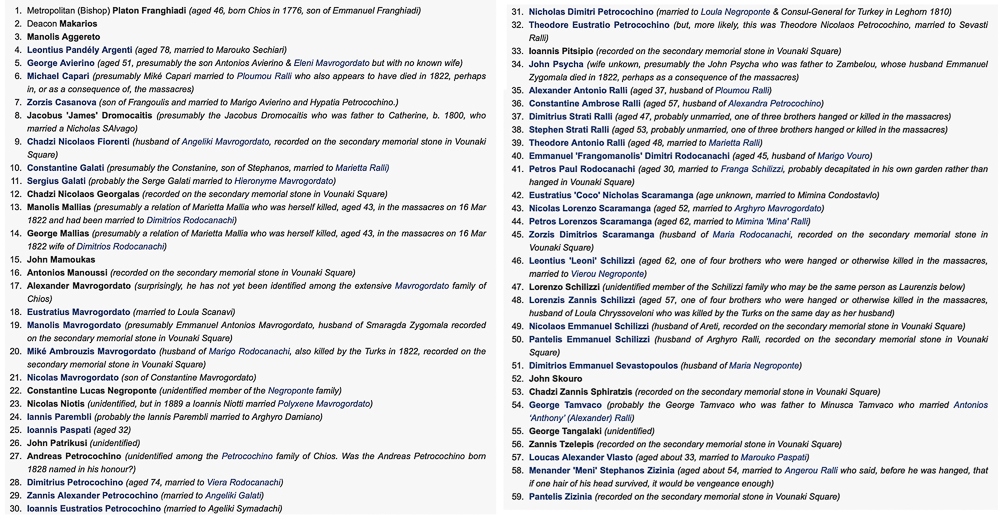

"In this dark dungeon in the year 1822, 74 members of noble Chian families were kept prisoner as hostages of the Turks, and from here on 23rd April 1822 after untold suffering, the Bishop of Chios, Metropolitan Plato, and 46 [sic] others were hanged: they died for their faith and for their country."

Today, beside the door of the grim gaol which contained up to 74 of the island's principal heads of family, a plaque records their fate on 23 April 1822.

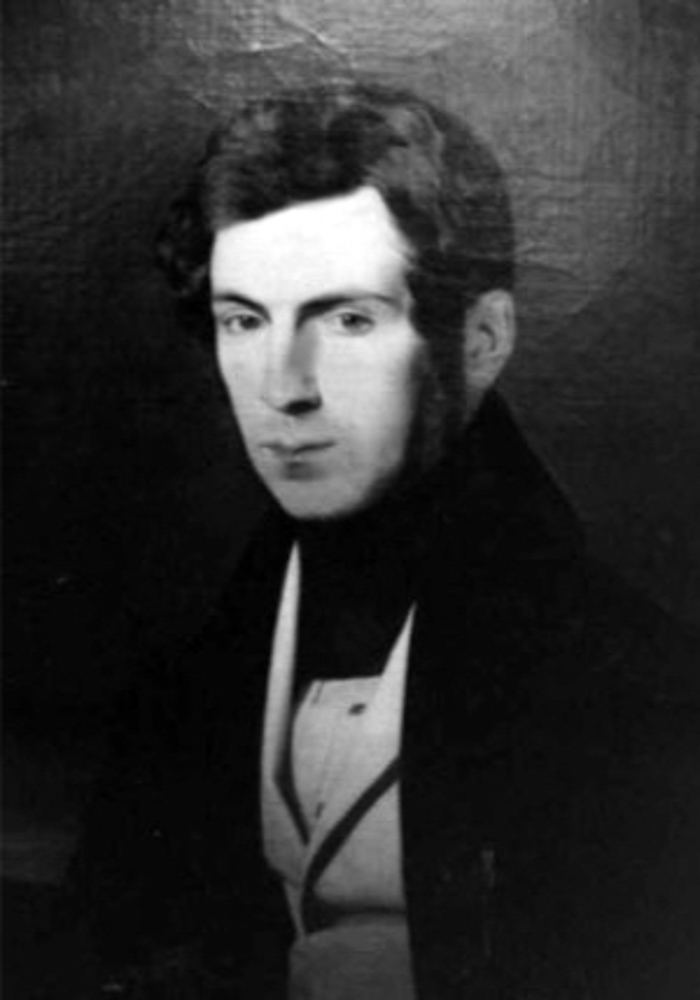

LOUCAS VLASTO 1789-1822 m. Marouko Paspati

As he prepared for his end he passed his Breguet watch, with Islamic numerals, to his cousin Michael. The author has it to this day. It was this that inspired him to learn more about Chios, its massacres and its diaspora,

At 10.00 a.m. on Sunday 23rd April at least fifty-nine men were to be publicly hanged. At the last minute Loukas Vlasto handed his Breguet pocket watch to his cousin Michael Vlasto – a watch given to me by my Vlasto grandfather in 1968.

The subterranean gaol in the Kastroin which around 74 hostages were held in 1821-22. Of these, 59 were selected to be hanged on 23 April 1822. To the right of the door is a plaque commemorating these grim events. This photograph was taken in 1999 when restoration works were in progress.

Bishop Platon Franghiadi and his deacon Makarios led the condemned men from their underground dungeon into the courtyard.

They were nearly naked, barefoot and with their wrists tied behind their backs.

They turned left and walked into the tunnel of the Porta Maggiore, turning left again a few metres further on, within the thickness of the massive Kastro walls.

Now ahead of them they would have seen sunshine pouring into the tunnel from the main gateway.

Here they turned right under the portcullis, across a drawbridge to the other side of a wide moat that no longer exists. They assembled in what is today Vounaki Square.

THE PORTA MAGGIORE

In 1822, a drawbridge crossed a moat around the Kastro (a channel extending from the port). The gateway led into what is, today, Vounaki Square.

Some remaining wives, family and servants were among the crowd gathered to witness the event.

A MEMORIAL TO SOME OF THOSE HANGED ON 23 APRIL 1822

A second memorial nearby records some of those who were not mentioned on the principal marble column in Vounaki Square. Subsequent research suggests as many as 59 men were hanged, mostly heads of households from among the island's most prominent families.

The gibbets stretched along what is now known as the Way of The Martyrs, from the Porta Maggiore to where an obelisk in marble from Skyros now stands by a fountain close to the walls of the Kastro.

On 17th May 1822, Francis Werry wrote to London with a graphic description of the massacres, as well as the plight of around 45,000 surviving women and children from Chios who were being sold into slavery in Turkey.

Now came the execution in Constantinople of the three prominent Chian leaders imprisoned there more than a year earlier: Theodore Eustratius Ralli, Michael Schilizzi and Pandely Rodocanachi, along with seven others.

THE ORIGINAL OTTOMAN FOUNTAIN CHIOS IN THE 18th CENTURY

This fountain did not survive the 1881 earthquake and was replaced. However both marked approximately one end of a line of gibbets stretching away to the main gateway to the Kastro along which 59 heads of family were hanged on 23 April 1822.

Lord Strangford in Constantinople wrote to London: "... the Ten Sciot Hostages residing here, were publicly beheaded. They were all persons of good repute, great connections in trade, particularly with the English merchants, and of large and honourably acquired fortunes..."

And on 17th May, Francis Werry wrote to Lord Strangford: "My Lord... the ferocity of the Turks... was carried to a pitch which makes humanity shudder. The whole of the Island... presents one mass of ruin. The unfortunate inhabitants have paid with their lives, the price of their ill-advised rebellion. The only persons who have been spared are the women and children, who have been sold as slaves."

THE 59 HEADS OF FAMILY HANGED IN VOUNAKI SQUARE ON 23 APRIL 1822.

This includes the names on the two memorials plus those known from subsequent research.

Few people ever described their experiences of 1822. The subject was still a deep taboo when I was a child in the 1950s. In 1968 only Philip Argenti could tell me anything at all. For 150 years each traumatised generation protected the next from such painful memories.

When my mother and I were researching her book about the massacres, Greek Fire, in the late 1980s, no one alive had anything to offer. But by then, our generations were very keen indeed to know what had happened.

As we saw, it was the richer families who escaped most easily and this may explain why many made provision in their Wills to provide schools and hospitals on Chios. But for the same reason many family members were prime targets for ransom. It's often forgotten that for many years to come families were searching for women and children taken as slaves.

LOUKAS GEORGE ZIFFO 1800-1876 m. Despina Capari

His story of returning to Chios soon after the massacres to pay Despina Capari's ransom inspired the novel 'Loukis Lara' by Demetrios Vikelas.

The best known of these was Loukas Ziffo because his story inspired a novel, Loukis Lara. He returned to Chios, paid a ransom to liberate Despina Capari and then married her.

Antonios Benachi's experience was more complicated. When he fled into hiding with his siblings and their children, all were captured by Turks and he was enslaved as a cabin boy by an ex-employee of his father. Eventually he took over the boat which allowed him to track down all his sisters except two. One of these returned to Chios many years later, having had two sons with her Turkish captor. And even Antonios's future wife, Loxandra, had been captured by the Turks aged six and taken to an Egyptian harem. There she was found and bought back, having been identified by a beauty spot between her eyebrows.

IOANNIS 'JOHN' SCHILIZZI 1805-1892 m. Alexandra Mavrogordato

Educated at the Academy of Chios, he was imprisoned on Admiral Karoli Pasha's ship in 1822 for 11 months. His family paid his ranson of 500 drachma and he then began a business in Livorno. A founder of the Greek Orthodox Cemetery at West Norwood. His mausoleum at West Norwood Cemetery was listed by English Heritage in 1981.

Although not a slave, Ioannis 'John' Schilizzi was held on board the Turkish admiral's flagship for eleven months until his family paid his ransom of 500 drachma through the Russian embassy in Constantinople. But his sister Franga was less fortunate...

FRANGA SCHILIZZI 1801-1851 m. Petros Rodocanachi

She may have been the writer of a surviving letter which describes her having to witness her husband being beheaded. This and other letters from survivors, imprisoned or fleeing, were collated and published in London and Edinburgh, but the names of the writers were anonymised, presumably to protect them from Turkish retribution.

... it may be she who described in an anonymised letter how she and her husband were held in the Kastro for ransom but that he was beheaded in front of her. She then bought her freedom for 800 piastres. She would have been twenty-one at the time.

PANDIA RALLI 1809-1860 m. Despina 'Pipina' Ralli

Bought back out of slavery.

The historian Peter Calvocoressi says two of his great-grandfathers were enslaved.It took relatives ten years in each case to find them and buy them back, in one instance, for the price of a ring. One of them was this Pandia Ralli and the other Matthew Calvocoressi who describes in his memoirs, A Grandfather's Story, how he and his sister, Zambelou, were enslaved.

A hero in all of this was Michael Petrocochino who rescued several children from slavery in Asia, among them two year-old Aikaterini Petrocochino. Michael may also have been the saviour of Cornelia Rodocanachi, aged twelve, who was bought back from a rich Turk in Smyrna, returning her to her family in Livorno. Another of his rescues may have been Loxandra Schilizzi, whose father was hanged in Vounaki Square.

Chance seems to have played a role too. George Petrocochino was on business in Marseilles, when his wife Despina and baby daughter were taken as slaves. Pretending to be a Turk, he found his wife and bought her back. But there was no sign of the child until, one day, Despina was hanging out her laundry and recognised her daughter's clothes a few houses away. They bought her back and immediately left for Marseilles.

HANIM RODOCANACHI 'of Chios' Elderly in the 1870s m. Unknown.

She was the mother of Hekim Ismail Pasha, a doctor and statesman in Turkey 'of Greek origin'. Presumably she took an Islamic first name when she became the wife of Hekim's father. She might have been a teenager in 1822. The photo was taken in the 1870s.

And 'slavery' came in different degrees. Hanim Rodocanachi, 'of Chios', was probably an adolescent in 1822 and, willingly or not, became the wife of a Turk. She took an Islamic first name and had a son who was to become a distinguished doctor and statesman in Turkey. We don't even know whose daughter she was...

CONSTANTINE 'COSTI' RALLI 1821-1889 m. Jeanette Psycha

"I myself was sold as a slave."

The final word goes to Constantine Ralli, from Liverpool, who asked his children in his Will to marry Greeks of the Orthodox faith, to help their mother country and not to forget that 'our relatives perished unjustly at the hands of the Turks'. He then reminded them: 'I myself was sold as a slave'.

I'm sorry there was so much sadness in all that. But we're halfway through our story and so let's move on to the more positive tale of how our refugee forebears rebuilt their lives.

DESTINATIONS INCLUDED: SMYRNA, SYROS, CONSTANTINOPLE, ALEXANDRIA, LIVORNO, VIENNA, TRIESTE, MARSEILLES, LONDON, LIVERPOOL, MANCHESTER, MOLDAVIA AND WALLACHIA

These figures are only useful as a guide to the relative sizes of each destination. The numbers do not include the many people for whom we have no birth or death dates and some we know nothing about.

It's important to remember that we're are talking about a tiny number of 'our' families – there were only ever about 1,000 of them over five generations. About 700 of these were alive at the time of the massacres, about 500 of whom survived.

The ships sent from Psara to collect refugees were far larger than this and probably capable of taking hundreds at a time. But this painting Flight From Chios by Francesco Havez was intended to convey the vulnerability and distress experienced by the refugees.

I doubt whether more than 400 actually clambered into rescue boats from Psara, their gold, their jewellery and their precious documents, all hidden in the time-honoured fashion of refugees. From Psara, a fortunate few went straight to Trieste, Livorno or Marseille, if they had the right connections, but nearly everyone else headed south-west to the island of Syros.

SYROS

THE ISLAND OF SYROS

A diaspora community of 349 (1822-1922)

57 born on Chios before 1822 and died on Syros

So here we are on Syros, an island in the Cyclades under French protection and here the refugees created a 'new' Chios with its own church, cemetery, schools and hospital where the Chian community grew to about 582 expatriates. They renamed the town Hermoupolis in honour of Hermes, the god of commerce, and mostly they prospered.

ALEXANDRIA

ALEXANDRIA

A diaspora community of 267 (1822-1922)

28 born on Chios before 1822 and died in Alexandria.

I have records of 497 people who were born, baptised, married or buried here.

Which leads us to Alexandria because it was mostly refugees from Syros who responded when the great Alexandrian 'cotton rush' beckoned – an Egyptian equivalent of the American Gold Rush. In the 1860s the Confederate states imposed export tariffs against Britain and so, for the next 100 years, Egyptian cotton of a better quality, largely filled the gap.

EMMANUEL BENACHI 1843-1929 m. Virginia Choremi

The son of a Chiot father who fled to Syros, made great fortune in Egypt and finally gave his house and its contents to Athens, to form one of the grandest museum Greece.

Most of the familiar Chios names turned up in Alexandria to supply cotton to Liverpool and Manchester but now lesser-known Chian families joined the élite. These included people like the Zervoudachis, the Choremis and the Sevastopoulos while in the case of the Benachis, their Athens home and vast fortune were eventually large enough to found one of the grandest museums in Greece.

C. P. CAVAFY 1863-1933

Generally regarded as one of the world's greatest poets. His family originated in Constantinople and he spent a few of his school years in Liverpool, but he was born and spent his adult life in Alexandria.

All that came to an end in 1956 when President Nasser nationalised the Suez Canal and foreign-owned businesses. This prompted many leading Greek industrialists and their families to leave Egypt.

PENELOPE BENACHI 1874-1941 m. Stephanos Delta

One of many fascinating Alexandrian figures, the writer Penelope Delta.

So, they upped sticks and left, often heading to Athens. I remember it well because suddenly our guests at home in England numbered exotic cousins, in exotic cars, smoking exotic cigarettes and speaking excitably in three exotic languages all in one sentence, each with an Alexandrian accent.

The other obvious destinations for our Psara and Syros refugees were Livorno, Trieste, Marseille and London, but before I talk about those, I need to tell you about the five Ralli Brothers.

THE RALLI BROTHERS

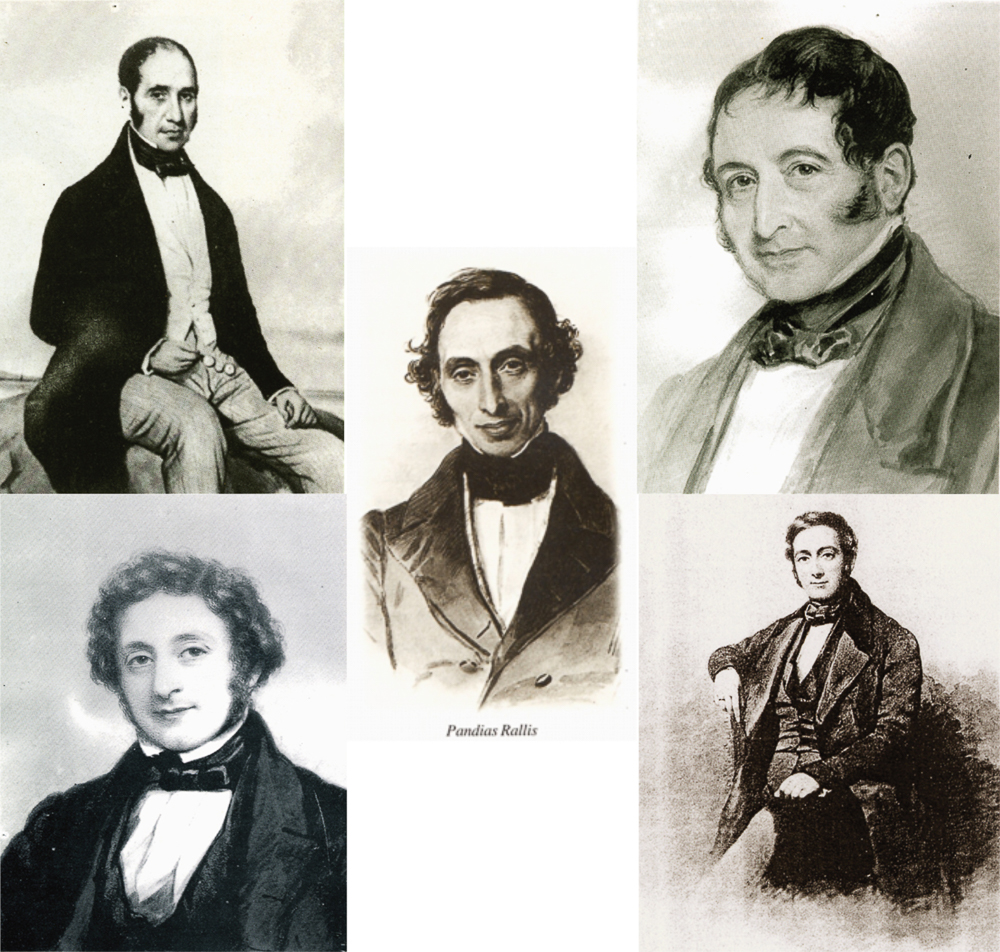

THE FIVE SONS OF STEPHANOS RALLI 1755-1827 m. Loula Sechiari

EUSTRATIUS (1800-1884 m. Maria 'Marigo' Mavrogordato), PANDIA (1793-1865 m. Marietta Scaramanga), AUGUSTUS (1792-1878 m. Sozonga Ralli), THOMAS (1799-1858 m. Maria 'Marouko' Argenti) and JOHN (1785-1859 m. Lucia Storni)

Now follow me carefully because just for a moment we're going to before the massacres.

Stephanos Ralli was the father of five sons and five daughters. Following Napoleon's defeats at the battles of the Nile in 1798 and Trafalgar in 1805, he realised that Britain ruling the waves would make maritime trade easier and safer. So, in 1805, he and his eldest son John opened an office in Livorno, to avoid Napoleon's tariffs on his Russian grain trade. Meanwhile, his cousin Ambrouzis was doing the same thing in Trieste.

ZANNIS 'JOHN' RALLI 1785-1859 m. Lucia Storni

Founder of Ralli & Petrocochino in London in 1818 and of Ralli Brothers, London, in 1826. He spoke English with difficulty but is sometimes credited with being the real founder of the firm Ralli Brothers when he noted that the majority of his Livorno clients were English traders. Later on he headed the Ralli Brothers' Odessa branch where he was US consul (1831-1861) and ennobled in 1840 and 1852.

Then, following the Battle of Waterloo in 1815, Stephanos and his son John noted that the centre of European gravity was London. So, in 1818 – remember, this is a few years before the massacres – he sent his five sons to open branches of the family business in London, as well as Odessa, Constantinople and Marseilles. The London firm was called Ralli & Petrocochino, trading in grain among other commodities from the Black Sea and Turkey. By pure chance this decision was to be the salvation of numerous Chian survivors and was to propel the Rallis and their associates onto the world's stage as global entrepreneurs.

EUSTRATIUS RALLI 1800-1884 m. Maria 'Marigo' Mavrogordato

With his brother John, he co-founded Ralli & Petrocochino in London (1818) but in 1826 with his brother Pandia the firm became Ralli Brothers with offices in Finsbury Circus. He was a founder of the Hellenic Enclosure cemetery at West Norwood in 1842; of the first Greek Church at London Wall; and of the Baltic Exchange Company in London in 1858. He lived in Hyde Park Square and later built a house called 'Scio' (Chios) on Putney Health.

Meanwhile, by about 1818, Stephanos must have known about the impending war of independence because he settled his family in Marseilles, so avoiding the massacres. Only his daughter Ploumou remained on Chios with her husband where he was to be killed by the Turks.

TOUMAZIS 'THOMAS' RALLI 1799-1858 m. Maria 'Marouko' Argenti

He ran the Ralli business in Constantinople and was a guild member in Odessa in 1839 and honoured there in 1853. In the 1850s he lived in Belgrave Square, and was well known for his humanism and kindness.

Now following the massacres, John was in Odessa handling the Ukraine and Russian end of the business, while Eustratius and Pandia took care of London, Augustus managed business in Marseilles and Thomas controlled Constantinople.

AUGUSTUS RALLI 1792-1878 m. Sozonga Ralli

Responsible for Ralli Brothers business in Marseilles, he built a country house near the Prado in Marseilles. It was his son Stephen Ralli (1829-1902) who built St Stephen's Chapel at the Hellenic Enclosure in West Norwood in memory of his son, Augustus Ralli (1856-1872), who died of rheumatic fever while at Eton College.

So, by a strange quirk of fate, a new firm of Ralli Brothers, founded in 1826, was perfectly placed to offer support to the surviving refugees – nearly all of whom were successful merchants in their own right, kinsmen of the five brothers and well known and trusted by each other.

PANDIA RALLI 1793-1865 m. Marietta Scaramanga

A founding partner of Ralli Brothers in London in 1826, he was largely responsible for developing the company into an international trading giant. Known as 'Zeus', he was universally acclaimed the leader of London's Anglo-Hellenic. He was a founding member of the Baltic Exchange Company, London (1858), Greek Consul General and president of the Greek Committee for Prince Albert's Great Exhibition in 1851. He lived in Connaught Place and had a country house, the Château de Bonne Veine outside Marseilles.

Ralli Brothers thus acquired skilled collaborators with expertise and invaluable contacts. By merging trading activities and acumen they could exploit new opportunities, notably in India. The family firm grew exponentially as a sort of Chian cooperative, cleverly harnessing the capabilities of their cousins, all of whom had experienced loss and tragedy in 1822 and all of whom urgently needed to rebuild their lives and fortunes. Many of us here this evening owe a great deal to this chance circumstance.

LIVORNO

LIVORNO

A diaspora community of 70 (1822-1922)

45 were born on Chios before 1822 and died in Livorno.

In total we have records of 166 members of the diaspora community in Livorno.

So now we can visit Livorno and get back to our refugees. Livorno was the principal port of the Grand Duchy of Tuscany and an obvious destination since Chiots already had trading links here. But it became unhealthy and the port declined when it lost its free trade status in 1861.

COUNT MIKÉ MAVROGORDATO 1817-1892 m. Semira Mavrogordato

His offices on the quay in Livorno survived but his villa was a ruin by the end of the C20th.

Only a small spectrum of the diaspora families settled here but well-established families like the Mavrogordatos and Rodocanachis were ready to help them.

THE RODOCANACHI PALAZZO IN LIVORNO

The much abused Rodocanachi family home by the end of the C20th.

The banker Emmanuel Rodocanachi had married Oriettou Vlasto on Chios when he was twenty-three and she fifteen. They escaped the massacres with their three babies but she died of exhaustion on arrival in Trieste.

GEORGE 'GIORGIO' RODOCANACHI 1795-1846 m. Amalia Benucci

Banker for Lord Byron, he encouraged Byron's support for Greek independence alongside his first cousins Emmanuel Rodocanachi (1794-1865 m. Oriettou Vlasto) and Paul Rodocanachi (1807-1891 m. Anna Boscovic).

Emmanuel then moved to Livorno to work with his younger brother Paul and their first cousin George Rodocanachi. Among their clients was Lord Byron.

LORD BYRON 1788-1824

He became a champion of the Greek bid for independence, encouraged by his Rodocanachi bankers in Livorno and their kinsman Prince Alexander Mavrogordato.

George seems to have encouraged Byron to support the Greek War of Independence and Byron certainly poured vast sums of money into the cause.

And it was probably through Paul that Byron met Prince Alexander Mavrocordato, a leader of the Greek rebellion, who went on to become the first president of the Greek nation.

JENNY RODOCANACHI 1851-1911 m. Matteo Mavrogordato

Daughter of Pandely & Catina Rodocanachi of Livorno.

Strangely enough, Mary Ann Chadwell, a governess engaged by Lord Byron for one of his daughters, was soon to become governess to the children of Pandia 'Zeus' Ralli in London. It was a tight little world!

DR ALEXANDER M. VLASTO 1814-1844 m. Joanna Rodocanachi

He was the author of Xiaka, a history of Chios which contained a notably restrained account of the massacres of Chios which he witnessed as an eight year-old. He became a doctor because of what he had experienced.

Also in Livorno was Dr Alexander Vlasto. An eight year-old eye-witnesses to the massacres, he grew up in Trieste, became a doctor, but practiced medicine in Livorno where lethal diseases were rampant. And it was here that he wrote his famous history of Chios, Xiaka.

TRIESTE

TRIESTE

A diaspora community of 238 (1822-1922)

91 were born on Chios before 1822 and died in Trieste.

In total we have records of 479 members of the diapora community in Trieste.

And so we head to Trieste, an Austrian empire free port in the Adriatic, which was an excellent destination for those with connections.

THE QUAY, TRIESTE

And it was familiar to many Chian merchants who had traded there successfully for some time.

Baron AMBROSIOS RALLI 1798-1886 m. 1. Anastasia Mavrogordato 2. Penelope Petrocochino.

He had thirteen surviving children of his own and also brought up the seven children of Theodore & Marietta Ralli, Theodore having been hanged by the Turks in 1822.

The grandest of these was surely Baron Ambrouzis Ralli. He was ennobled by the Austrians who were grateful for his development of the port. Several other merchants, like the Economos and Rodocanachis, were similarly created counts and barons.

THE CHURCH OF SAINT NICHOLAS IN TRIESTE

As one might expect of merchant traders, their church was on the quay beside the port.

As everywhere, the community set about providing its own infrastructure. Ambrouzis was a leader in the construction of the community's neo-Classical Church of St Nicholas on the quayside...

THE GREEK HOSPITAL IN TRIESTE DATES FROM THE C18TH

It survives to this day, although the roofline has now been altered. There was also a school, thought to have been a part of the hospital.

... its own hospital, still standing today... and a school. Facilties like these become increasingly important as the colony expanded.

THE SCARAMANGA TOMB

In the delightful Greek Orthodox cemetery set high on a hill outside Trieste.

In addition they built a glorious Greek Orthodox cemetery on a hilltop overlooking the Dalmatian coast, where we first met Michael Vlasto. In terms of artistic quality, some of these monuments at least match those in our own Hellenic Enclosure.

THE ECONOMO PALAZZO ON THE QUAY IN TRIESTE

As in Livorno, family businesses had their offices and warehouses close to the quay, some of which have survived, like this one which belonged to the Economo family from Macedonia...

THE ECONOMO FAMILY HOUSE IN TRIESTE

Home of Baron Dimitrios Economo (1870-1951 m. Janie Ralli)

... although in the case of Dimitrios Economo, the family also had a private country house separate from the business, as did other Rallis and the Rodocanachis.

THE GALATI PALAZZO

The Galati family from Chios was among the most numerous in Trieste. They included Dimitrios Galati (1784-1836 m. Zambelou Scaramanga) and Toumazis Galati (1763-1838 m. Ageliki Negroponte). This building combined business and domestic accommodation.

The Galati family, on the the other hand had a palazzo that seems to have served as offices and a family home following the mediaeval pattern.

PANDELY MAVROPGORDATO 1780-1855 m. Zennou Vlasto

He seems to have remained on Syros until 1849 when, aged 69, he settled in Trieste with his wife Zennou.

So as we leave Trieste, it's hard to look at this picture of displaced Pandely Mavrogordato without noting the pain in his face. He had survived when so many of his family had not.

ZENNOU VLASTO 1795-1872 m. Pandely Mavrogordato

She seems to have spent her final years in Livorno with her brother Petros and sister Franga.

And one could say the same for his wife Zennou Vlasto, the daughter of Michael the demogeront, although she had also lost three of their six children in infancy.

ANGELIKI VLASTO 1837-1869 married EUSTRATIUS PETROCOCHINO 1822-1897

He was born at sea off the port of Trieste. She was the daughter of Petros Vlasto and Caterina Ralli and died during the birth of her seventh child. Her portrait is by G. F. Watts.

And perhaps this afternoon some of you noticed the tomb of Eustratius Petrocochino in the Enclosure stating that he was 'Born at Sea'. His father, Manolis, one of the few Kastro hostages to survive, fled to Trieste with his wife Alexandra Ralli with a child in arms. Eustratius, their second son, was born on 12 June 1822, just outside the port of Trieste.

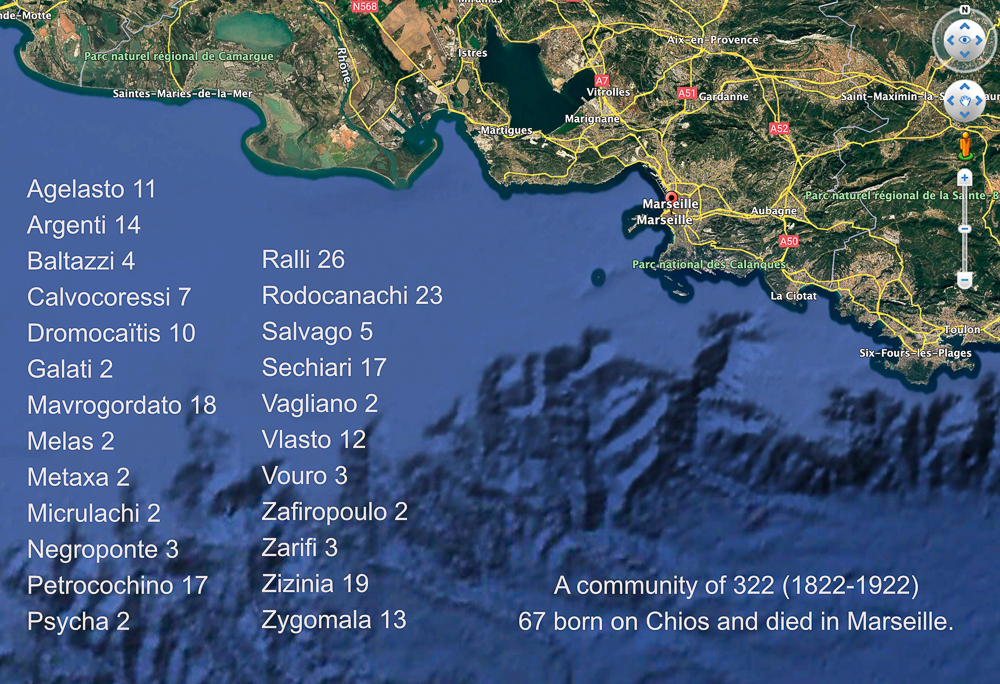

MARSEILLES

MARSEILLES

A diaspora community of 322 (1822-1922)

67 born on Chios before 1822 and died in Marseille.

Our records show 619 people who were born, baptised, married or buried here.

And so we sail for Marseilles where I have happy youthful memories of visits to cousins. Marseilles became the diaspora's most important base in continental Europe. Here the familiar names – Rodocanachis, Argentis, Vlastos, Sechiaris, Petrocochinos, Rallis and Scaramangas – were joined by formidable Phanariot bankers from Constantinople such as the Zarifis and Zafiropoulos, the Baltazzis from Smyrna and ship-owners like the Vaglianos from Cephalonia.

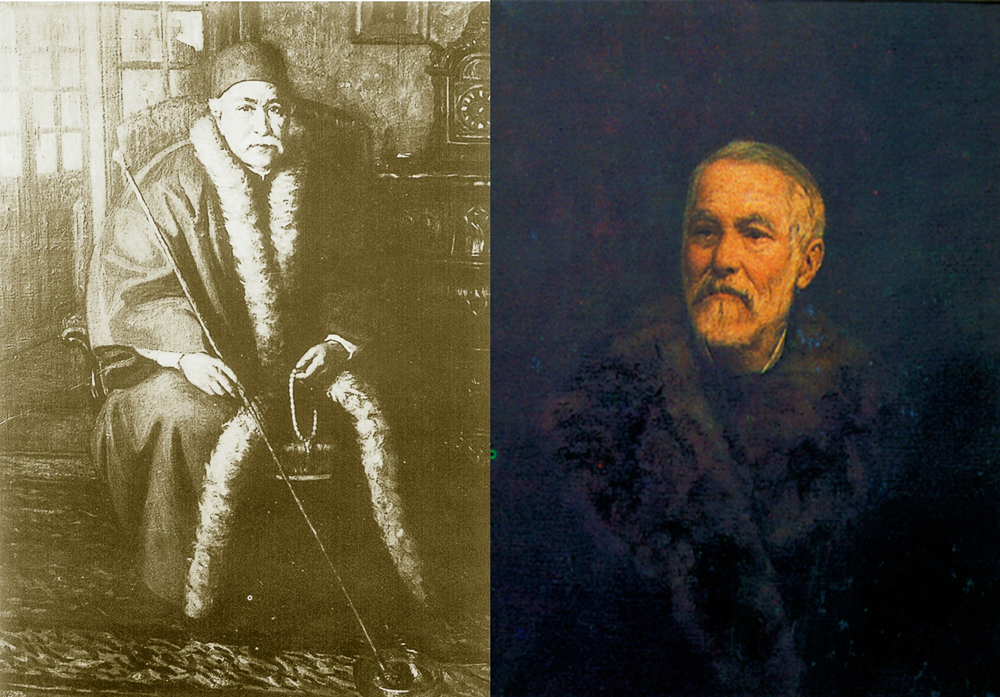

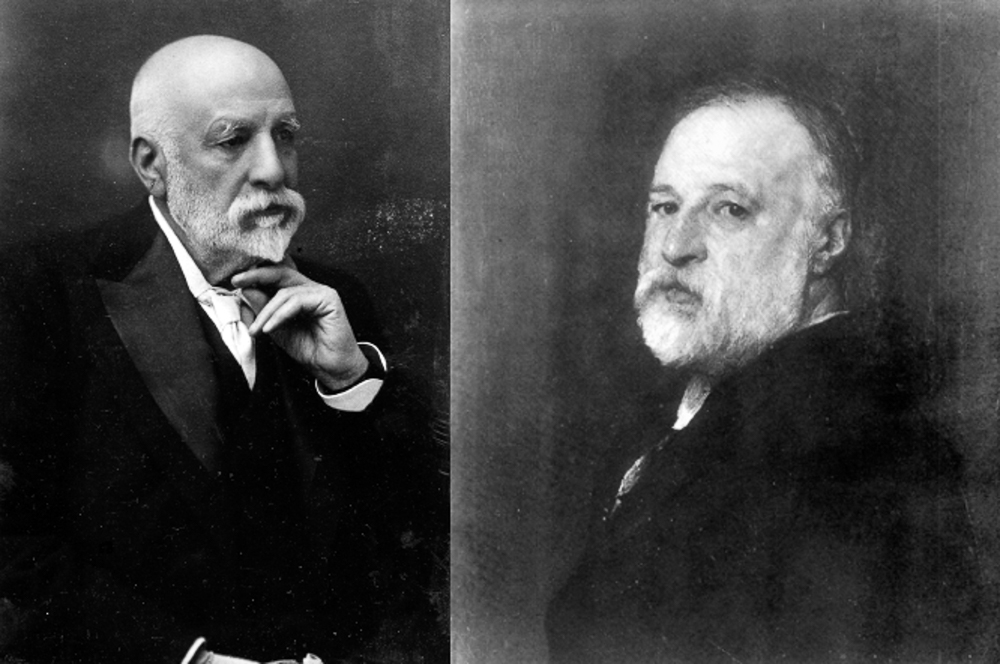

DIMITRIOS ZAFIROPOULO 1770-1864 m. Rallouka Fenerlis

+ GEORGE ZARIFI 1807-1884 m. Eleni Zafiropoulo

Demetrius (left) in a portrait by his children's Italian art teacher, was from Ioannina and made a fortune in Constantinople as a banker in association with George Zarifi (right)) along with Leonidas Zarifi in Constantinople, Pericles Zarifi in Marseille and Michael Zarifi in London.

This is Demetrius Zafiropoulo who, with his son-in-law George Zarifi, created a merchant bank with branches in Odessa, Constantinople, Marseille and London during the C19th and C20th. It became vital to the economy of Marseilles and, through Zarifi Brothers in London, to the development of sophisticated merchant banking in the City of London.

Top left: GEORGE ZARIFI 1807-1884 m. Eleni Zafiropoulo

Top right: MICHAEL ZARIFI 1818-1891 m. Fanny Kessisoglu

Bottom left: THEODORE ZARIFI 1873-1949 m. Netta Vlasto and LEONIDAS ZARIFI 1840-1923 m. Phrosso Nicolopoulo

Bottom right: THEODORE ZARIFI 1858-1910 m. Alexandra Ralli) and JOHN ZARIFI 1856-1919 m. Marigo Rodocanachi

The Zarifi holiday house on the Bosphorus and the Zarifi family home at 441, Avenue de Prado, Marseilles.

Together, they could handle the entire process of financing, purchasing, lading, shipping and marketing cargoes autonomously among themselves, all the way from, say, the Black Sea to London.

THE ZARIFI MAUSOLEUM IN SAINT-PIERRE CEMETERY, MARSEILLE.

And their model was simply a modern version of the Genoese Chian method of the 15th century. In simple terms the method required that a number of investors in a tight circle, with guaranteed liquidity, each invested in each other's shipping ventures as principals or underwriters. Many such ventures needed to take place at any one time in order to limit exposure to risk.

In 1909, HÉLÈNE ZARIFI 1882-1976 married ETIENNE EUGENIDI 1879-1957

The reception was at the Zarifi family holiday house at Therapia on the Bosphorus. Such marriages were nearly always arranged, strategic and in a sense dynastic.

No outsider could be involved, which required 100 per cent trust between partners – which is why, of course, you married your daughter to your partner's son who was of course your second cousin. This sort of thinking was to inspire the underwriters of Lloyds in the City of London just as much as it appealed to the criminal tendencies of the Sicilian and Neapolitan mafias in the USA.

A BANKING DYNASTY: THE ZARIFI, ZAFIROPOULO AND VLASTO FAMILY

Photograph taken either in Constantinople or Marseilles, ca 1896.

In fact, the skills of Marseilles bankers and merchants so eclipsed those in Paris that when France colonised Algeria in the 1830s, it fell largely to the Chiots and Phanariots of Marseilles to supply grain from the Black Sea to the huge French army in Algeria and the growing colonial population of pieds noirs.

THE GREEK CATHEDRAL IN MARSEILLES

The names of family sponsors inevitably included: Rodocanachi, Salvago, Scaramanga, Sechiari, Vagliano, Valieri, Zafiropoulo and Zarifi.

In the 20th century, family banks of this sort played a large part in arranging French loan requirements to finance the First World War and, in more recent times, financing the Nouveau Port in Marseilles and motorway infrastructure in southern France.

But we're short of time, so I'm going to mention just four remarkable individuals from Marseilles – each of them active in Occupied France during the Second World War – two of whom survived and two who didn't.

DR GEORGE RODOCANCHI 1876-1944 m. Fanny Vlasto

A founder of the WWll escape and evasion network, Pat Line which helped over 600 Allied servicemen get out of Occupied France and back to Britain to carry on the fight. His apartment was the network's HQ and principal safe house. He was betrayed and died in Buchenvald concentration camp.

Dr George Rodocanachi and his wife Fanny Vlasto were founders of Pat Line, a WWll escape network used by British and other Allied servicemen who were trapped or shot down in Belgium or France. The line hid them and got them back to England to carry on the fight. Pat Line had its headquarters and main safe house in the Rodocanachi's large apartment in the Rue Roux de Brignoles.

FANNY VLASTO 1884-1959 m. Dr Georges Rodocanachi

Christopher Long's first visit to the Hellenic Enclosure, West Norwood, was for Fanny's funeral in 1959.

Fortunately this apartment also contained George's consulting rooms which provided good cover for the comings and goings of over 600 men who were hidden and given false papers and improvised cover stories before being guided over the Pyrenees into Spain and so back to England.

SAFE HOUSES ARE DANGEROUS by Helen Long.

From 1940-1943, the network stretched from Lille in north France, involving scores of volunteer couriers and helpers. Inevitably British intelligence services adopted it and this probably contributed to the recruitment of potential traitors. In the end George was betrayed, arrested and died of exposure in Buchenvald concentration camp on 11 February 1944. Many other members of the line were executed by the Germans too.

HÉLÈNE 'ELAINE' VAGLIANO 1909-1944

A courier helping Allied intelligence gathering on the Côte d'Azur.

The other person who deserves special mention is Hélène Vagliano, known as Elaine. As the war developed, she moved from Marseilles to her parents' holiday house, the Villa Champfleuri, near Cannes. There she became a courier passing messages for British intelligence in London. She hid these in the tubes of a wheelchair used by her haemophiliac brother Stephen. Eventually the Germans arrested and cruelly tortured her in numerous attempts to extract the names of other resistance workers.

THE VAGLIANO VILLA, CHAMPFLEURI, NEAR CANNES

Here Elaine Vagliano's parents entertained German officers obtaining useful information for British intelligence services. Unknown to them their daughter was a resistance courier.

Sadly, her parents were made to witness some of this. Later she was shot. Ironically her parents had not been aware of their daughter's resistance work although they themselves had been entertaining senior German officers in order to obtain information to be sent to London.

PANDELY ARGENTI 'Père Cyrille' 1918-1994

A resistance worker in Marseille during the German Occupation, he became the city's Greek archbishop (archimandrite).

The fourth cousin, who was to survive his remarkable resistance work in Marseilles, was Pandely Argenti, better known as Father Cyrille, later to become archbishop of Marseilles. His biography has just been published and it was it was he, incidentally, who baptised me into the Greek Orthodox church in the gardens of 441 Avenue du Prado in 1954.

THE MARRIAGE OF HELENE ZARIFI WITH PANDELY VLASTO

Just another of those dynastic marriages... with the author's mother, Helen Vlasto, in the centre as a bridesmaid. Marseilles 1932.

Dynastic marriages were still securing family fortunes well into the C20th, as for example this Vlasto-Zarifi wedding in Marseilles in 1932 where my eleven year-old mother is a bridesmaid. But by the turn of the century, some young Rodocanachi daughters were sufficiently integrated into France that they and young French aristocrats slipped effortlessly into each other's arms, just as young Rallis, Vlastos and Ballis were doing in England.

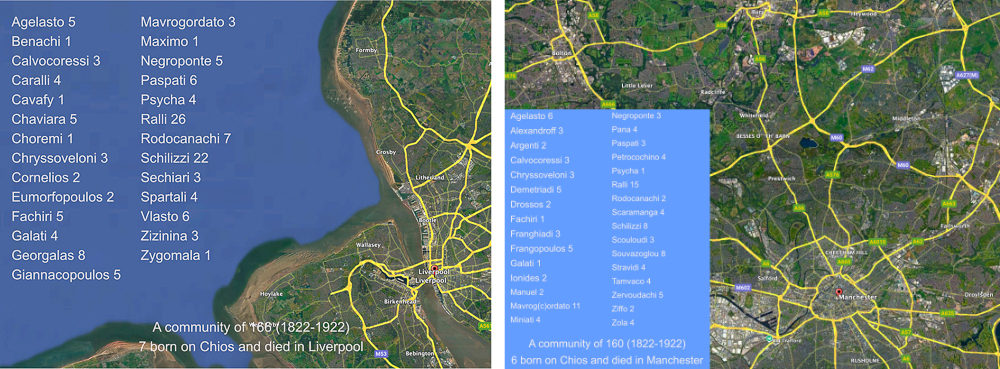

LIVERPOOL & MANCHESTER

Liverpool: A diaspora community of 166 (1822-1922)

7 were born on Chios before 1822 and died in Liverpool

Manchester: A diaspora community of 160 (1822-1922)

6 born on Chios before 1822 and died in Manchester

And now we head for Liverpool and Manchester. I'm not going to be saying very much about these two very important Hellenic colonies for the very good reason that the master of the subject is sitting with us here this evening.

THE GREEK COMMUNITY OF LIVERPOOL

By S. B. Williams, who is currently working on a study of the Greek community of Manchester.

Steve Williams has produced an excellent book on the Greek community of Liverpool and if he weren't here, skiving with us this evening, he would be busy on his new book on the Manchester Greeks.

LIVERPOOL & MANCHESTER FAMILIES

These supplied Ralli Brothers with its partners and directors and were largely the source of the company's success.

All I need to say is that while Ralli Brothers and others had their head offices and banks in the City of London, the partners and directors in Liverpool and Manchester were the driving force behind the worldwide success of the company. All the familiar family names were here, but they were now joined by new, energising arrivals from Constantinople and Smyrna. Among the most successful of these were the Demetriadi, Alexandroff, Fachiri and Spartali families.

THE RALLI BROTHERS WAREHOUSE IN LIVERPOOL IN ca 1951

Some of those who worked for Ralli Brothers, as chairmen, managing directors, partners or managers. Senior partners worked at the London headquarters and with the merchant banks, while others managed operations in Liverpool, India, the USA and elsewhere.

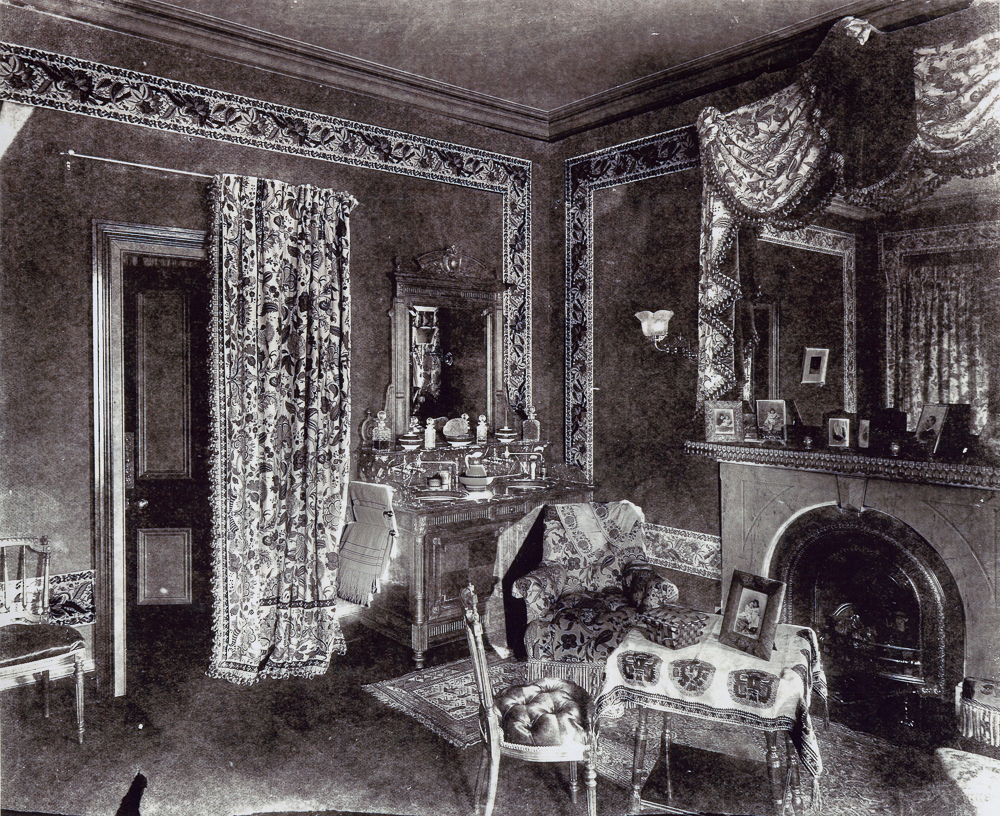

But before we leave, I want to show you some interior decoration. If you've ever wondered how life was lived in an Anglo-Hellenic household, here are a couple of examples:

GEORGE CONSTANTINE RALLI 1858-1910 m. 1. Antonia Ralli 2. Elizabeth Cornelios.

Dressing room at his house 'Iona', Liverpool, 1891,

In 1891, Bedford Lamar photographed the interiors of three huge houses in Liverpool – two from the Ralli family and one from the Vlastos. As you can see, they remained strongly influenced by the furnishings of the Genoan-Ottoman houses their owners remembered from 60 years earlier. These, for example, are rooms in George & Antonia Ralli's house...***

AMBROSE VLASTO (1837-1897 m. Anastasia Rodocanachi)

Morning room at his house 'Gunavah', Liverpool, 1891.

... while these belonged to Ambrose Vlasto and his wife Anastasia Rodocanachi whose great-great nephews (a Michael and two Anthonys) are with us this evening.

It needs imagination to paint in the vibrant colours of these rooms – consisting of the richest and most sought-after silks and woven textiles that Persia, the Caucasus and Manchester mills could offer.***

And very quickly, here are another two examples...***

EUPHROSYNE 'PHROSSO' NICOLOPOULO 1856-1933 m. Leonidas Zarifi

At home in Pera, Constantinople, in ca 1886. The richness of the colours and opulence of the textiles can only be imagined!

And in case you think this is just Victoriana at its wildest, here's a picture of Euphrosyne 'Phrosso' Nicolopoulo at home in Pera, Constantinople, in about 1886. Constantinople décor would have inspired the Kampos villas in 1820 just as they did a morning room in Liverpool 60 years later.

GEORGE ZARIFI 1880-1943 m. Lili Krinos

His memoirs, written in Greek, will be available in English in 2026.

And we may soon learn a lot more about this Constantinople influence because Phrosso's great-grandson, Ari, is with us this evening and currently working on an English translation of his great-uncle George Zarifi's memoirs of a Greek-Ottoman life.

THE USA & INDIA

HELLENIC DIASPORA FAMILIES ESTABLISHED IN THE USA.

Many were there for reasons unrelated to the cotton industry.

And so to the cotton-rich southern states of the future USA. These Confederate states might have played a huge role in our Hellenic diaspora story but for their Civil War. Unbelievably, tariffs or blockades were imposed to stop cotton exports to Britain and this denied the future United States a vast export market.

NICHOLAS MARINOS BENACHI 1810-1886 m. 1. Catherine Grand 2. Anne Marie Bidault

Builder of the colonial style Benachi House in New Orleans in 1859, he was a pioneer in the cotton business in the Southern States and built the first Greek Orthodox church in the New World and was Greek consul.

Nevertheless, several families made their futures and fortunes in north America in the 19th century, with Nicholas Benachi among the first.

I'm still not sure how and why forty-two Rallis and considerable numbers of Mavrogordatos, Franghiadis, Fachiris, Zizinias and Negropontes established themselves in the USA. My suspicion is that Ralli Brothers at least was ever hopeful of seeing important trans-Atlantic trade, but young thrusters unsurprisingly found other lucrative opportunities in the New World. Our cousin John Negroponte, recently US ambassador to the United Nations, was in my view among the best presidents the US never had.

ALEXANDER AGELASTO 1835-1906 m. Polyxene Mavrogordato

He famously figures in 'A Cotton Office in New Orleans' by Edgar Degas as the man in a hat, to the left, leaning on the cotton table.

Cotton inevitably takes us to the Agelastos, best known to me because Michael has been an invaluable collaborator in our family history project. And because his great-grandfather, Alexander, features prominently in a famous Edgar Degas painting of a New Orleans cotton office. I'm delighted to say that Peter Agelasto, another great-grandson is with us this evening, with his son, another Peter.

It's one of my aims for next year to learn a great deal more about all this, hopefully with the help of cousins here present.

LONDON

LONDON

A diaspora community of 552 (1822-1922)

37 were born on Chios before 1822 and died in London.

And now now we're in London and into the home straight – with 20 minutes to go. When our diaspora arrived in the first half of the 19th century, London was becoming the trading capital of the world.

CONSTANTINE 'IPLIKTZIS' IONIDES 1775-1852 m. Mariora Sentoukakis

The first to arrive was probably Constantine Ipliktzis Ionides of Constantinople who settled here in 1815. By 1830 he was at No. 9 Finsbury Circus and, soon after, nearly everyone else established their business around him.

FINSBURY CIRCUS IN THE CITY OF LONDON

Anglo-Hellenic companies in or around Finsbury Circus included:

Ralli (6), Scouloudi, Argenti, Sechiari, Spartali, Lascaridi, Schilizzi, Negroponte, Rodocanachi (2), Hadjimoissi, Mavoyeni, Cassavetti, Karati, Ziffo, Franghiadi, Geralopoulos, Mavrogordato, Scanavi, Tamvaco, Microulaki and Ionides. The Ionides house at 9 Finsbury Circus contained a room used by the growing Hellenic community as a chapel for baptisms.

Constantine imported textiles, yarns and fibres from Turkey, trading with the Theodore Ralli who was to be one of those 'three prominent men' killed by the Turks in May 1822.

Left: ALEXANDER IONIDES 1810-1890 m. Euterpe Sgouta

Right: CONSTANTINE IONIDES 1833-1900 m. Agathoniki Fenerlis

Brilliant businessmen and passionate about the arts. They were patrons to many contemporary artists whose work they collected. They also commissioned portraits of their families by artists such as G. F. Watts

However it was his son Alexander Ionides and grandson Constantine who formed the world-class collection of contemporary and old master paintings, prints and drawings that was eventually presented to the Victoria & Albert Museum and which I'll show you in a moment.

The first wave of diaspora families were of course our refugees. But these were followed by a second wave from Smyrna and Constantinople who came by choice. We met the Alexandroffs, Spartalis and Demetriadis in Manchester, but now the Zarifis, Ballis, Baltazzis, Kessisoglus and Eugenidis were settling into London.

Ralli Brothers, as we saw, had became a sort of Chian 'collective', working with in-laws or close cousins throughout the Mediterranean and Black seas. But in 1851 the firm opened offices in Calcutta and Bombay, importing jute, shellac, sesame, turmeric, ginger, rice, saltpetre, and borax, employing 4,000 clerks and 15,000 warehousemen and dockers. By the time of the First World War their factory in Dundee had a virtual monopoly on the jute sacks used in hundreds of miles of frontline trenches.

THE BALTIC EXCHANGE

Took its name from the Virginia & Baltick Coffee House in Threadneedle Street in the City of London. It revolutionised merchant trading and shipping. Members of the Rodocanachi, Ralli, Scaramanga and Vagliano families were among its leading founders and shareholders.

But all this required a transformation of the City of London. To operate profitably a market-place was needed for the sale and purchase of cargoes in transit, with a parallel futures market and an efficient shipping market that matched available ships with attendent cargoes and destinations.

PANAGHIS VAGLIANO 1814-1902 m. Catherine Vegdatopoulos

They lived at 16 Dawson Place, Bayswater and she was presented at the Court of St James.

Here Panaghis Vagliano from Cephalonia with his brothers Marinos and Andreas were to revolutionise shipping, as did the Embiricos family. This paved the way, a hundred years later, for the likes of Onassis, Niarchos and dozens of shipping magnates ever since. And now is the moment to say a special word of welcome to both Sonia Vagliano and Christina Kulukundis!

THE BALTIC EXCHANGE COMPANY